|

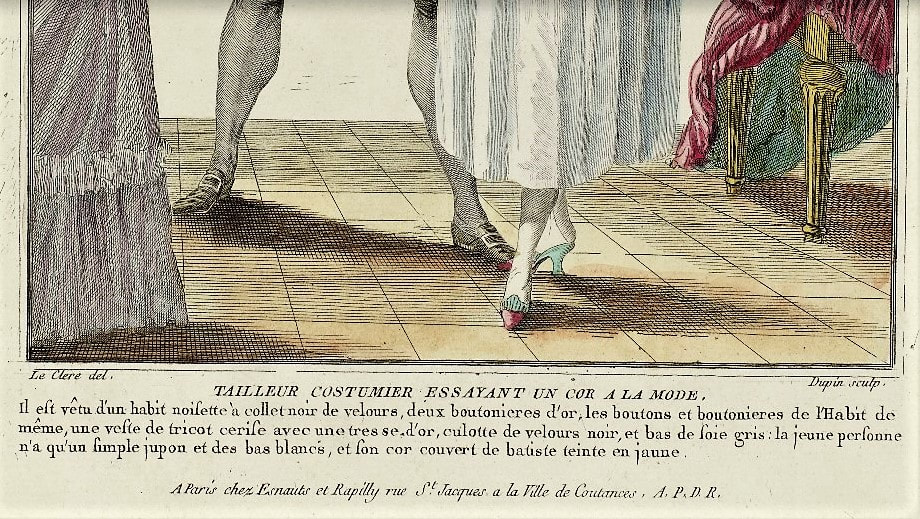

Absorbing Surprises in Historical Costume (a.k.a. Fashions that shouldn't exist) As a fashion historian I always try to be aware of what I call “absolutism” when thinking about or discussing historical costume. One of the easiest and most enticing traps to fall into where historical dress is concerned (particularly for time periods prior to the mid-19th century) is making unconditional statements or conclusions based on what is necessarily a limited supply of evidence. I've always believed that the further back in time one goes, the less justifiable it is to indulge in "fashion absolutism", i.e. rule-making. This is often proven true with the sudden appearance on the open market of an historical garment in a style or construction that "should not exist". Avoiding such difficulties is essentially a matter of seeing beyond what might ordinarily seem to be settled borders of history. Put another way, it means training the eye and mind to accept what is really there, sometimes without being able to fit an item neatly into a previous category. This is especially the case where the 18th century is concerned, in fact for any time prior to about 1860, when photography and mass-market print publications became widely available, giving us a more direct window into what people wore. As I've mentioned in other articles I've posted on this site, I find that it's typically the privately listed historical garments that get the most thorough photographic attention, and as such are far more helpful to a costume historian than many museum photographs are (personal viewing of extant garments aside). The photograph below (from a private online auction listing), which gives a rare view of the interior construction of the bodice of a ca. 1770-75 gown in a silk/cotton striped textile, is a good example. In fact, often even the descriptions of privately sold garments are more detailed than those given by museums for similar garments. From the photograph below it's possible to see and study quite a number of period construction techniques which can inform further study or the making of reproduction garments. Privately owned or listed antique garments that come on the market can accordingly be very illuminating -- even surprising -- in their variety and detail, sometimes to the point of proving that what experts think was "likely not seen" in a particular era did indeed exist. If nothing else, they frequently provide a glimpse into what sort of clothing was worn by people who were not in the upper class, in other words, the average person's dress. These are quite often garments that come out of everyday middle-class estates, tucked away for decades in a dark trunk in someone's attic by an unrecorded ancestor before being brought up for auction. I would define “historical absolutism” generally (that is, not specifically where costume history is concerned) as a tendency to make definitive, final, or rather permanent statements or conclusions about some aspect of history based on what is necessarily a rather small sampling. This is particularly a pitfall where 18th century fashion is concerned, since study is frequently limited perforce to just a handful or two of surviving examples or paintings. I think it’s a natural human desire (or at least a natural modern one), to want to categorize, classify, label, and pigeon-hole new things once we’ve already seen a few that appear to conform to a type. The file then gets closed and put away as case solved, with little inclination to revisit the matter. The natural tendency is to ignore or dismiss as odd – if not impossible – any item or information that subsequently appears which doesn’t fit the established parameters. This is indeed I think the definition of a mental trap. In fairness I must add that many reputable costume historians are careful to use qualifiers and circumscription when describing their findings, allowing them to revisit, modify and revise earlier conclusions when new evidence comes to light. This is a more rational and even scientific method than closing the door permanently on a particular subject and stashing it away as complete and resolved. Put simply, where costume history in particular is concerned, one garment (or even a handful of garments) does not always a fashion rule make! I so often see online comments stating: “this-or-that was not done or seen”, or “such-and-such wasn’t worn or didn’t exist”, sometimes even with “never” or “always” added, which only magnifies the problem. Yet the truth is (and I believe most professional historians would agree), the further back in time we go, the less we can be certain of any definitive, final statement about history and historical dress. So what feeds into this compulsion to “close the case”, and how can it be avoided, particularly by amateur enthusiasts of the subject? One important factor that I believe tends to encourage “historical absolutism” is a failure to recognize how narrow and uneven a slice of contemporary fashion we have in extant 18th century garments, particularly those held by world museums. It’s not an exaggeration to say that our understanding of historical dress based on extant 18th century garments themselves can be skewed due to the limited number of surviving pieces (largely in museum collections) and the reasons for which they survived. Both museum selection criteria and – long before items reach museums – personal motives for retaining and preserving particular garments, colour our view of 18th century fashion. Museums tend to purchase “important” pieces representing a time period and the height of design or embellishment. These rare and beautiful pieces are often selected because they are in good (or excellent) condition for display and longevity purposes. These are certainly magnificent garments, often amazingly well preserved, and without a doubt worthy of attention and study. Most originated with wealthy, prominent or aristocratic families, not generally representative of middling or lower class dress. As a whole, such collections depict a small segment of 18th century society. In this respect, such gowns are not unlike most of the beautiful garments captured in 18th century upper class portraiture. From our viewpoint, it's like looking through a narrow slit at a large painting and trying to understand the entire picture. Not only are such collections often weighted toward the higher class of dress, but museums do occasionally get the dating, or the mounting and display of a costume wrong, which can further add to erroneous conclusions by viewers. It’s also important that every piece of historical clothing be situated in an understanding of its original geographical and social context, which means researching a broader field in order to judge how typical a garment was for its time and place. Regional differences in dress (and other areas of life) were more pronounced in the 18th century than they are today in our era of mass-media and frequent travel. A style worn in a portrait in ca.1750 southern France for example, might be quite out of place and even unknown (that is, not worn), in England at the same date. It’s essential to be able to recognize when these factors apply to any historical garment. One example follows, a ca.1703 painting entitled La Belle Strasbourgeoise byNicolas de Largillière, although many more exist. Before deducing anything from this portrait in relation to conventional European dress of 1703, a thorough investigation of the history and costume of the Strasbourg region would need to be done. You would discover for example that this area passed from one European power to the other (mostly French and German) for centuries and was influenced by both. Deeper research would no doubt reveal further information about the costume shown in this fascinating image: Here is another example, a ca. 1745-50 painting entitled “Portrait of a Jacobite Lady” (byCosmo Alexander). Any conclusions about this lady’s style of costume vis-à-vis typical English costume would need to involve research into the history of Scottish dress of the middle to upper classes of the period (few people of the lower classes could afford to commission a formal portrait). A proper consideration of this costume would likely also require research into military dress of the period. Further, the dress of ordinary folk (i.e. those above the poor, but below the wealthy) are generally not well represented in terms of their proportion to finer clothing in museum collections, or indeed in paintings. Part of this is likely because “ordinary” costume was not as worthy of careful preservation, and was simply discarded or used for other purposes once worn out or hopelessly unfashionable, leaving fewer surviving examples. For these types of clothing, we really only have the occasional glimpse provided by artists who depicted “everyday” life, or by the often tangential evidence of written documentation. Another factor compounding the issue of how to think about historical dress is what is sometimes called “preservation bias”. I don’t particularly like this term because it suggests that the bias exists around what is preserved or why, in other words a bias at the origin point, rather than a bias in our thinking about and observing preserved garments. Bias at the origin point may sometimes certainly be a factor (the owner liked blue better than green, long better than short), but it’s not the whole story. Happenstance, fate, and whimsy can often play just as important a role in whether a particular garment is carefully saved by the original owner, and later by their descendants or others. We should acknowledge that sometimes garments are put away and saved because they were unusual, or because they represented a particular moment in an owner’s life, or – more prosaically – because they were simply forgotten, not necessarily because they were a typical example of contemporary fashion. All of this is not to say that we can’t reach some broad, generalized conclusions about fashion and style in a given time period and place. But these always need to be tempered by a recognition of the often limited number of pieces available for study, and qualified in terms of exceptions to what seem “typical” costume of the era. In short, qualifying terms such as “more” or “less”, “generally”, “frequently” or “rarely”, “likely” or “unlikely”, “usually” or “unusually”, and so on, are more appropriate to any discussion of historical dress than words like “never”, “not”, or “always”. Lastly, avoiding historical absolutism means having a willingness to fit a new discovery into an established picture of 18th century clothing. I’m always struck – and fascinated – by the occasional item from the 1700’s that surfaces in private sales or auctions. These items frequently “break the mould” of what we may think we know about fashionable clothing in the 18th century. They cause us to look with fresh eyes and should remind us to think twice about making “never” or “always” statements about historical dress. A few examples follow which illustrate the sort of items that might prompt a rethinking of some commonly held views of costume history, in these cases of the 18th century. Whether such items were high fashion, made by professional tailors or gown makers, or else home-made garments, really matters very little. Someone felt they were appropriate and/or fashionable to wear in their place and time. A recent example that interested me were these 18th century European velvet stays, listed on an online retail selling platform. This garment is unusual in several ways, certainly not typical, yet there it is, forcing us to bend our view of fashion conventions of the 18th century just a little… Here is another instance of a surprising item in private hands, a man’s ca. 1770-75 suit (from the famous Tasha Tudor collection, most of which was sold at auction a few years ago). The unusual aspect here is not the cut of the suit, but the textile from which it was made, described as printed velvet, a textile I had not noticed in men’s 18th century suits before. (Following this full-length photo is a cropped version that gives a better view of the surface of the velvet itself.) And another example: a spectacular, fully quilted sacque gown (robe à la française), ca.1750-60, from the collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute. It might be hard to imagine that such a complex garment requiring such skill in execution, completely quilted, yet made closely along the lines of contemporary silk gowns, could exist had this extant not survived. Another styling that appears to break the usual 18th century rules is shown in the lovely ca.1750 portrait of the Marquise de Caumont La Force below, by Drouais. We’re accustomed to seeing fur trim on pelisses and cloaks, but surely fur trim on a gown, not to mention the addition of odd-looking lace sleeves, could not be right! It looks to be a very odd costume. And yet, the Marquise apparently wore it (and liked it well enough to have her portrait painted in it): You might be tempted to say that the previous painting was surely a one-off oddity of personal taste (and therefore easily dismissed) but further research reveals that might not be the case. This is where established “rules” of 18th century dress and a tendency to lean towards finality (i.e. absolutism) can become a hindrance to a broader understanding of period costume. Once you find an aberration, it’s important to research around the edges, so to speak, to see if that particular feature of style can be found elsewhere or in a similar form. In this case in fact, it seems this mode was not unique, for here is the Marquise de Pompadour herself, from about the same period in France, with fur trim on her gown (collection of the Musée du Louvre): The use of fur trim rather than ruching, furbelows or lace, also appears later, ca.1780-85, in a portrait of Marie-Antoinette (by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun). Interestingly, this is not the only portrait of Marie-Antoinette wearing a gown with fur trim: You might be inclined to conclude, based on the above portraits, that this fashion of using fur to trim gowns was only a French idea. But it’s worthwhile to keep an open mind and a sharp eye to look further, for here is a portrait of Lady Holland, ca. 1765, by Allan Ramsay. Notice that even the flounces are trimmed with fur. Having seen the above images, it’s hard to be completely confident making statements about what and wasn’t usually employed as trim on 18th century gowns. Whether the ca. 1770 portrait below (of the Maréchale de Bellisle, by Quentin de la Tour), depicts fur or feather trim on this sacque gown is hard to determine – it’s certainly one or the other. Notice that the bodice also has the short sleeve tops and tiered lace sleeve flounces like those seen in the Drouais portrait above. While these styles may not fit into our typical expectations of mid- to late 18th century dress, they clearly existed, and merit study of their historical context. Doing so might result in a revision of our belief of what was fashionable or typical in 18th century upper class French dress. For the time being however, these paintings can remind us to keep an open mind. I think that whenever one unusual garment is found, we should be willing to admit the possibility that there might have been others, rather than dismissing the unusual item off-hand as freakish, atypical or wrong. Still, it’s true that placing such garments in a proper historical and social context can be a challenge. For example, understanding whether the French gowns shown in these portraits were strictly gowns donned for formal portraits or court attendances, or whether they were worn for normal dressy events such as dinners, receptions, visits, etc., would take much more specific research. This ca.1750-70 completely feather-covered bergère-style hat, in the V&A (Victoria & Albert Museum) collection provides another example of teaching the mind to see beyond the usual conventions of costume history. This may at first seem like an impossibly odd or unique variation on hats of the era. Was it perhaps even someone’s unique and weirdly aberrant idea of personal style? However in fact another amazingly similar chapeau from the era exists in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which you might not know about without digging a little deeper on the subject: A little further research turns up a depiction of what appears to be just such a feathered hat in this ca.1745 painting by Philip Mercier entitled “The School for Girls”. So now we have at least three examples, and it’s impossible not to admit that there could have been others at the time. Accordingly, we might need to revise our views on the materials and embellishments used on mid-18th century ladies’ hats. Conventional wisdom on 18th century hat styles is that straw “bergère” hats with pretty ribbons and sparse trimmings were the height of style, but it’s quite possible that these feathered hats were just as fashionable and typical. Before concluding that they are bizarre anomalies, we need to consider the possibility that there simply weren’t enough of them that survived in proportion to straw hats. The moral of this lesson? Be careful about jumping to conclusions where historical costume, especially before the mid-19th century, is concerned. I think by now you may see where I’m going with this: if we draw immutable, permanent lines around what we believe we know, we’re unlikely to be able to absorb and admit new information into our overall picture of historical fashion. In other words, it’s important to keep an open mind and be willing to drop old concepts once new examples appear, even if they don’t fit the expected types of an era. I also believe it’s useful to bear in mind that people may have applied their own personal interpretation to contemporary fashion, while still remaining within the boundaries of what was acceptable at the time. I don’t think the 21st century has a monopoly on creative dressing. Next is a rather subtle example of personal taste combining styles of different periods (certainly not the only one I’ve encountered though!). This is a robe à la française of ca.1755 (privately sold), with a very up-to-date compère (false vest) front of the type seen in other gowns and portraits of the period, yet with the older exaggerated “manches à la raquette” (racket-shaped cuffs). The gown was listed as being unaltered from its original state. It seems that the original owner decided she would like a slightly older style of cuff on her gown, along with the new compère style. I’ve reproduced this gown myself (see details in my website Blog), mainly because I found this personal mix of newer and older so interesting. The wide, “tennis-racket” shaped cuffs can clearly be seen in the photos from the original sale listing, and in my reproduction of the gown: Another horizon-expanding example of 18th century dress is the ca. 1730-1750 embroidered linen robe à l’anglaise shown below, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Conventional historical costume wisdom would suggest that mid-18th century floral-sprigged gowns could only be made of silk brocade, in which case this gown would represent an oddity, perhaps to be dismissed within the usual boundaries of 18th century fashion – someone’s home project perhaps? The fact that extant gowns of this type may be very rare in collections today doesn’t prove that they weren’t both fashionable and possibly even more common than we might imagine – we simply may never really know. To continue the earlier metaphor, this file should remain open. A further example of an embroidered linen gown (from a later period), is shown below, from the LACMA (L.A. County Museum of Art) collection, dated ca.1760. This time the embroidery is executed in wool (see close-up photo). Now we begin to wonder, given these two examples from completely different decades, how rare embroidered linen gowns really were. Or, we can ponder, if they weren’t rare or bizarre at all, was it only an accident of fate that so few were preserved? We can also leave open the possibility that these garments may have actually been made (i.e. re-purposed) from embroidered draperies, etc., rather than originally embroidered as gowns. The example below seems even more unusual and interesting, a ca. 1770-80 robe à la française made in a cotton textile referred to as “Indienne” (from its origin in India), with striking conifer tree motifs embroidered in wool. This was offered at private auction some years ago. This gown certainly fits the description of a garment that “shouldn’t exist”, but we’re forced by its presence, to absorb it into our overall view of 18th century fashion. One possible theory is that the textile used in this gown (perhaps like the previous two gowns) may have begun its life as decorative drapery, bed hangings, bed coverings, or other soft furnishing. The gown is a wonderful example of the kind of surprising and unusual items that can pop up in private collections or sales. They may or may not have been widespread or typical at the time, but we simply can’t conclude they were rare based only on the fact that few survive today. Once again, without further evidence (the likelihood of which is slim) it must remain an open-ended, unresolved case. All that can be said is that embroidered linen and India cotton gowns existed, but to what extent they were commonly made and worn at the time may never be known. It’s also possible, if we’re thinking “outside the box”, that embroidered gowns such as these might have been too useful as sources of home decoration not to be turned back into draperies or other furnishings in much later eras, which would be one plausible explanation for the scarcity of surviving examples. Lastly, there is the question of drawing conclusions about historical dress from contemporary paintings and sketches. Here I think the pitfalls are numerous. It requires a knowledgeable eye to sort out what is reality, fantasy, or artistic licence in 18th century art. This is a subject worthy of deeper consideration which I plan to address in a separate essay as Part 2 in this series. Suffice it to say that not everything depicted in 18th century paintings accurately represented 18th century fashion for the average middle-class or even upper middle-class person. One case in point is the loosely arranged, classically inspired drapery in this ca.1772 portrait of Ann Verelst, by George Romney. This has very little connection with contemporary dress of the period: Still, there is one incontrovertible truth about costume history: If a surviving item is found, then obviously it existed in its time. Provenance is important and fascinating, but mostly in the context of the particular garment. What one surviving extant can’t tell us however, without at least a few other similar examples or contemporary documentation, is whether that garment was common and/or considered fashionable. Certainly there are general themes and lines of fashion seen across numerous examples of surviving garments that are reasonable to deduce or hard to dismiss. Such things as the usual cut of gown sleeves along the horizontal pattern of a textile, the relative consistency of the shape and silhouette of the robe à la française through several decades, and the emergence of cotton textiles supplanting silk in the last quarter of the century, are examples of elements that are repeated widely enough in extant examples to provide some generally reliable outlines of 18th century fashion. However, if we keep an open mind, then previously unseen examples of 18th century dress can help to crack open our fixed (and sometimes misguided) concepts regarding historical costume. Such “anomalies” can also suggest that personal style preferences may have been more important than we will ever know. Accordingly, I think it’s with a certain arrogance that we claim that a particular mode of fashion could (or could not) have been done. That would presume that 18th century people (especially those with at least moderate economic status) were much less able to be creative in their dress than we are today. I find this premise hard to accept, which is why I believe a certain amount of freedom in reproducing 18th century dress, i.e. painting outside some of the lines, is more reasonable than we usually like to admit. This is why first-hand historical accounts and observations on fashion, as rare as they are, can be so critical, filling in and adding to the picture of fashion of a particular era. Such accounts frequently occur as mere incidental (even oblique) notes by an observer in a completely unrelated text, diary or journal, but are precious as an on-the-spot window onto a lost world. Some writers are better known for their skill and interest in observing such things, despite the likelihood that most had no awareness whatsoever of how incredibly valuable their few words on a contemporary fashion subject could be more than two centuries later! I like to keep my eyes open for such little treasures when reading first-person accounts or works on history that describe a scene which may include comments about fashions. If a person who actually lived at the time gives opinions on what was worn and considered acceptable fashion, we have to treat those opinions as some of the truest representations we have. I offer one further example of a garment that “breaks the mould” of conventional wisdom about 18th century fashion (at least at the beginning of the 3rd quarter of the century in France). During the course of some recent research, I came across what at first seemed a typical illustration of 18th century fashion, from the “Galerie des Modes” of 1778. This fashion sketch or trade illustration shows a tailor/costumier fitting stays on a young lady, apparently a rather ordinary subject depicting a tailor in the course of his usual work. At first I studied the illustration itself, which seemed to offer little beyond what I’d seen in other similar period sketches. What made this image interesting however, and what caught my attention, is that the brief description underneath mentions the stays are “covered in yellow coloured batiste”. Although silk can be made in a batiste weave, it's more likely that "batiste" referred to a fine linen (or possibly cotton) at this era. The word "batiste" is said to have originated in the 1400's, and is defined by my etymological French dictionary (Le Robert) as "toile de lin très fine", meaning a very fine (i.e. lightweight and finely woven) linen cloth. Summer stays covered with (cotton) batiste are a familiar Edwardian mode, but rarely considered in the context of the 18th century, where we tend to think of substantial linens being most suitable for hard-wearing stays. Batiste -- especially fine linen -- may have been a good choice for warm weather or summer wear. Another explanation might be that linen or cotton batiste, still rather luxury fabrics at this time period, may have had a certain cachet for the most fashionable women whose stays would not expect to get frequent or heavy wear. It's also plausible that the tailor who posed for this illustration was merely keen to show off his most fashionable novelty. Unfortunately for us, the printer of this illustration makes no mention of why such a fine textile was used. The textual description that accompanies the illustration in the "Galerie des Modes" sheds no helpful light on the particularities of the textiles used, aside from briefly describing the general construction of the stays. The illustration makes it clear (from our vantage point) that such a garment was not unheard of, and possibly not unusual. It’s demonstrated in the sketch as in the normal course of a tailor’s usual work. Nothing is said about the fine batiste covering being odd, bizarre, or new. Of course, the lack of commentary on this point doesn’t prove that linen batiste-covered stays were common, although the stays are shown on a fashionable-looking young lady with a very stylishly arranged coiffure. Take into account as well the fact that the title describes the garment as “Cor à la mode” (fashionable stays). Notable too is the fact that these are back-lacing stays with the addition of decorative front lacing, a fashionable touch. The text focuses (unfortunately) on the tailor’s own costume, but provides a second interesting insight, mentioning that his waistcoat is made of “tricot”, i.e. apparently some type of knitted material. Presumably a tailor would be a well-dressed fellow in the latest style, to properly represent his profession. Note too that he is wearing velvet breeches and is shown with a fine lacy jabot at his neck. Following is my translation of the text shown under the illustration (I am a former professional French/English translator, and the notations in square brackets are my own). Tailor-costumier* trying [i.e. fitting] a Fashionable Cor** “He is dressed in a nut-brown habit coat with a black velvet collar [trimmed with] two gold buttonholes, the buttons and buttonholes of the habit-coat matching, a waistcoat [vest] of cherry-red tricot [knit fabric] with gold braid trim, black velvet breeches, and grey silk stockings. The young lady is wearing nothing but a simple petticoat and white stockings, her Cor covered in yellow-dyed batiste.” *A “tailor-costumier” (tailleur costumier) during this period in France was, according to Garsault, a particular trade set out by statute, which involved not only stay-making for women, but also the making of gowns, riding habits, cloaks, etc. **The word “Cor” in French of this period was synonymous with “cors” or “corps”, meaning “body”, or in English of the time, “stays”. However, the French recognized different categories of “cors”, depending on the construction method and materials used. Here is another interesting point regarding the above Galerie des Modes stays illustration. The word "batiste" in French at this period (ca.1778) referred to a very fine, lightweight, quite sheer and glossy closely-woven fabric, originally (prior to the mid-18thC.) made of linen. However this was about the time when cotton was beginning to be more widely available (from the Americas). So it's quite possible the description "son cor couvert de batiste..." could refer to either linen or cotton. In fact, by around 1790, cotton batiste was more common, and by the early 19thC., the word "batiste" had migrated into English, where it became more or less equivalent in quality to fine, semi-sheer cambric. Apparently this 1778 French sketch even confused the authors of PoF5, as they opted in their book to describe the covering of these stays as "cotton" (see caption on sketch below). Whether a fine, semi-sheer cotton or linen covering is in the end not really relevant, since it was the fact that a lightweight, fine material was being used to cover the stays, something that at first glance seemed quite unusual. I also wonder whether I'm seeing ripples or ruching in the front of the stays covering, i.e. a gathered effect (zoom in to see what I mean), or if that was just sloppy illustrating technique? Whatever the case, this is an intriguing bit of costume of history! What this one little illustration demonstrates is how much a very careful analysis can reveal in important, maybe even essential details, and perhaps more interestingly, what questions it can raise, which in turn widen our view of historical dress. As an experiment, try taking a look at the collection of the types and styles of garments held by any large museum intending to represent fairly recent fashion, for example, from the 1980’s to late 1990’s. Scrolling through such a collection, I think it will be clear to anyone who was an adult during those years that these extant examples usually don’t provide a balanced or very accurate representation of the clothes worn by the average person, even the average fashionable person, at the time. Fortunately for historians of recent costume, there is a myriad of other sources to rely on, such as magazines, newspapers, television, films, personal photographs, and first-hand accounts about fashion. In the end, if we can keep an open, flexible mind, ready to incorporate new material into a more fluid view of historical costume, especially prior to the 19th century, it’s possible to avoid the mental trap that can shut out further, potentially important aspects of history.

Such a trap (whether it’s called “absolutism” or “conventional wisdom”) can seal surviving examples of costume into a sort of petrified image, and keep us from properly acknowledging -- or even recognizing -- new discoveries and absorbing them into an understanding of historical costume. So the next time you find what seems to be a bizarre aberration of 18th century fashion that "shouldn't exist", don’t dismiss it out of hand. Flag it for future reference, keep an open mind, and take the time to dig a little deeper!

1 Comment

25/11/2021 08:56:12 pm

Am very glad to see the subject of absolutism taken up. It's something humans seem to be so prone to do in so many situations.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPatricia Preston, a.k.a. The Fashion Archaeologist, Historian, linguist, pattern-maker, enthralled by historical fashion, especially the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.. Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed