|

Well, today is already April 2nd, but did you play a practical joke on a friend yesterday, or become the victim of one yourself? I know, I know – with so many deeply worrying things going on in the world today, it’s hard to be serious about being silly.

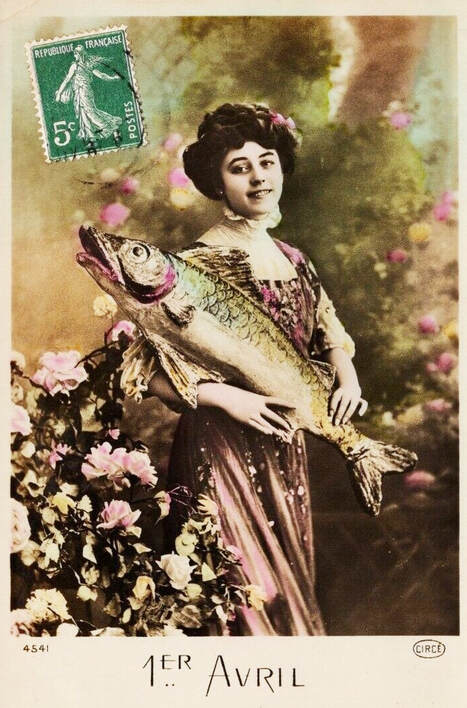

Yet April Fool’s Day has a very old, albeit obscure, history that few people know about. There are various contested and contradictory theories of its origin, including disputed connections with Chaucer, the zodiacal shift marking the beginning of spring in temperate climates, the 16th century change to the modern (Gregorian) calendar, the opening of fishing season in certain regions, and the most obvious – the Catholic period of Lent (with its relationship to fish). Most people today simply take it for granted that April 1st is the day for playing pranks, without wondering why that is. But it has a fascinatingly mysterious and convoluted origin.

0 Comments

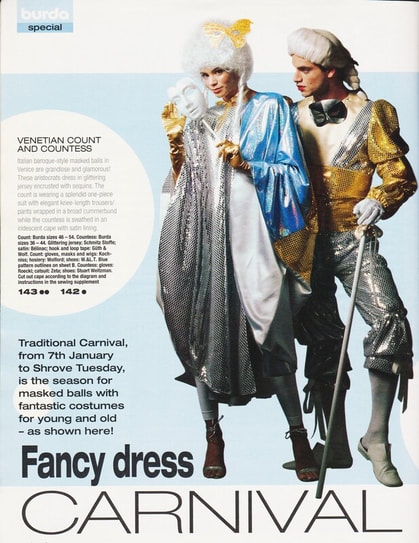

I’m always glad to say farewell to January, my least favourite month, with its cold winter blasts and the long, dreary, colourless weeks that follow the holiday season, devoid of anything much to look forward to. However, the Edwardian era knew how to mitigate that ennui! In the French fashion publications of the early 20th century that I work with in my research, the January issues always previewed fancy dress for the “Carnaval” or Mardi Gras season, and the anticipation of lively costume balls and dinners that were an integral part of it. From the 1890’s to the onset of WWI, French fashion magazines featured examples of, and patterns for, fancy (and “fantasy”) dress or disguises appropriate for the occasion, based on all sorts of creative whimsies. This certainly wasn’t a new concept, although these magazine articles and patterns specifically for fancy dress only began appearing after about 1900. The history of fancy dress balls or masquerades and the making of costumes for them of course goes back centuries. In fact it still continues with patterns offered for modern fancy dress -- readers of the German fashion magazine Burda will recognize the tradition in sewing pattern designs for Carnival season usually offered in their January publications, as in this January, 2004 issue: Likely because these carnivals were connected with the Catholic religious calendar, there seems to have been little focus on them in Edwardian British and North American fashion publications, as compared to their French counterparts. Nonetheless, judging from British and American reports and novels of the era (not to mention surviving costumes), the season of parties, dinners, and balls of the end of the 1890's and beginning of the 20th century was not without “fancy dress” or masquerade balls.

(Click on "Read More" at right to see the rest of this essay) Although I work regularly with antique publications that include a plethora of information on both fashion and contemporary life, it's rare to come across a detailed description of an historical dance pre-dating the early 20th century. In this case, the dance in question is the 'Gavotte', a dance which had peasant origins in the 16th century, but was transformed into a "danse galante" that became popular -- and even prescribed -- in the court of Louis XIV. A while ago, while researching another subject altogether, I happened upon an incredibly precise, step-by-step explanation (complete with a sketch) of how the Gavotte was performed in the 18th century (the word "performed" here is more apt than simply "danced", as the description gives the impression of a series of moves that could only be executed by the most practised and skilled of couples). The Gavotte is difficult to define, as it changed a great deal in character from its humble country beginnings as a type of French bransle, to a more structured 17th century dance, to its formal, courtly manifestation in the 18th century. One common characteristic is the stepping, rather than sliding motion of the dance. Bach particularly liked this form of music, and wrote many Gavottes, as did Rameau and Lully for the court of Louis XIV. It continued to be danced (and composed by musicians) for decades afterward. I was so impressed by this unusual article that I decided to translate the entire text from the original French, along with some notes on the music itself, which I've posted below; I've also included the source French article for those who would like to read it in the original language. Some of the references are now a bit obscure, but I've tried to make sense of them within the context:

Later on, I happened across an 18th century colour version of a very similar sketch to the sketch that had been used in the Edwardian article (shown above) to illustrate one of the steps in this dance (it's possible it may have come from the same 18th century publication). I've posted the colour sketch at top. (Funny how you often find just what you need by coincidence once your mind is focused on it!). I like to imagine that whoever it was that wrote this article ca. 1905 had access to technical information that is more direct than what we have today, perhaps through one of the last of the old dance-masters of the 19th century still practising in the early 20th (maybe the Professor mentioned in the article?), who had the skills and knowledge handed down from the courts of the last French kings. By 1905 it had long disappeared from formal ballrooms. For those who may want even more specifics about the Gavotte, there is an extensive review of its musical features and history of the dance itself on Wikipedia here:

|

AuthorPatricia Preston, a.k.a. The Fashion Archaeologist, Historian, linguist, pattern-maker, enthralled by historical fashion, especially the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.. Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

||||||

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by Dot5Hosting

RSS Feed

RSS Feed