|

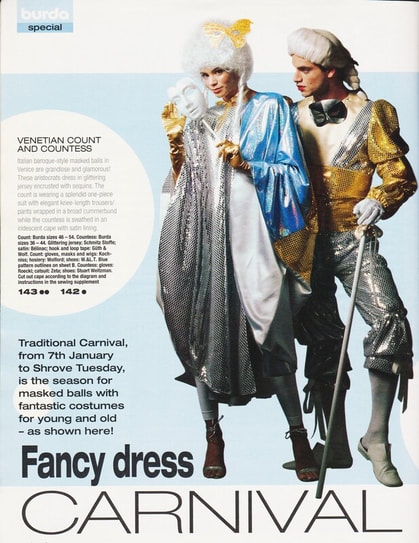

I’m always glad to say farewell to January, my least favourite month, with its cold winter blasts and the long, dreary, colourless weeks that follow the holiday season, devoid of anything much to look forward to. However, the Edwardian era knew how to mitigate that ennui! In the French fashion publications of the early 20th century that I work with in my research, the January issues always previewed fancy dress for the “Carnaval” or Mardi Gras season, and the anticipation of lively costume balls and dinners that were an integral part of it. From the 1890’s to the onset of WWI, French fashion magazines featured examples of, and patterns for, fancy (and “fantasy”) dress or disguises appropriate for the occasion, based on all sorts of creative whimsies. This certainly wasn’t a new concept, although these magazine articles and patterns specifically for fancy dress only began appearing after about 1900. The history of fancy dress balls or masquerades and the making of costumes for them of course goes back centuries. In fact it still continues with patterns offered for modern fancy dress -- readers of the German fashion magazine Burda will recognize the tradition in sewing pattern designs for Carnival season usually offered in their January publications, as in this January, 2004 issue: Likely because these carnivals were connected with the Catholic religious calendar, there seems to have been little focus on them in Edwardian British and North American fashion publications, as compared to their French counterparts. Nonetheless, judging from British and American reports and novels of the era (not to mention surviving costumes), the season of parties, dinners, and balls of the end of the 1890's and beginning of the 20th century was not without “fancy dress” or masquerade balls. (Click on "Read More" at right to see the rest of this essay) As a linguistic aside (and because linguistic history can often shed light on costume history), fancy dress or fantasy outfits were called in French at the time travestis (sometimes also travestissements). The word “travesti” has an interesting history. Its origin is the Italian “travestire”, from the root “trans” (across) and “vestire” (to dress), literally “cross-dressing”. No doubt travestire had already been a common entertainment in places like Venice long before it became popular elsewhere. It came down to English in the 19th century as “travesty”, meaning a false representation or distorted imitation, usually meant as a scathing ridicule or criticism of something (which itself says something about English mores of the 19th century). In modern times, the word “transvestite” appeared, as if full circle, it's meaning being actually closer to the original Italian. In any case, these “travestis” ensembles ran the gamut from imaginative and luxurious reproductions of the dress of earlier centuries, to fantasies of ideas, animals, historical characters, or everyday things expressed in creative costume. One French article of 1910 reports that dressing up in Japanese or Chinese costumes was now over-used and less in favour, whereas costumes “de style”, and especially those reflecting the period of Louis XIII, XV and XVI were now in fashion for fancy dress balls (why Louis XIV was omitted from this list is a mystery!). The same article recommends using new (i.e. purchased new) satins and supple brocades for these gowns, pointing out that these fabrics can later be re-purposed to make dinner or evening gowns, or an elegant evening mantel. Below is a rather rare photograph of a fancy dress ensemble from 1910, meant to depict a gown of the era of Louis XVI, described as being made of pink satin and white lace with a turban and neckerchief of silk chiffon. Here are some further examples of “Louis” costumes from ca. 1903 to 1910. Also popular, according to the writer, were costumes depicting characters from novels, plays, types of "traditional" or “peasant” costumes, or various historical of antique time periods – such as the ones below, which according to the article portray: an 18thC. flower girl, a well-known character from French literature (“Manon”), a “Dutch costume”, an “Alsatian woman”, and two "ancient" costumes (presumably Greek or Roman) respectively:

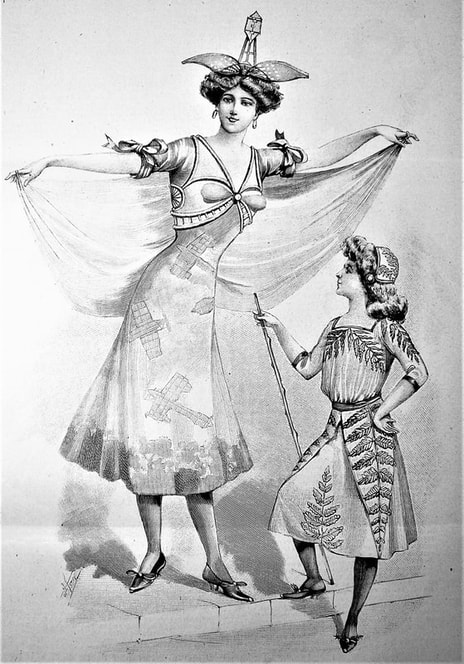

A great deal of money – sometimes enormous sums -- could be spent on these outfits, as well as on the lavish balls that highlighted them, hosted by some of the most prominent members of the “beau monde” of the day. One of the highlights of this fad was the much-publicized fancy dress ball of 1911, organized by Paul Poiret, in which harem pants and other Turkish styles were featured (akin to the runway promotional extravaganzas organized by couturiers today). Although this was a novel idea in 1911, it had sprung at least in part from the influence of orientalism through the Ballets Russes and Stravinksy’s groundbreaking works. Clearly this sort of fancy dress ball was an entertainment reserved for the wealthier classes. Newfangled, modern inventions also captured the imagination of makers of fancy dress for these balls. Below are examples: the first costume, from 1909, depicts "aeroplane" -- such as it was at the time -- (along with a child's "fern" costume), the second, from December 1912, the concept "electricity", and the last (a rare photo) from about 1910 of a remarkably creative merry-go-round costume. Still, the middle class wanted its fun too! It seems, judging from one helpful French magazine article of January, 1910, that the expense for attendees in creating their costumes had got to such a level that thoughtful hosts and hostesses had to come up with ways of curtailing the financial burden. The article reports that attendees at many balls were now being asked to make their fantastical costumes out of paper rather than costly fabrics (it’s mentioned that these were usually supported on percale or muslin foundations -- as hard as that is to picture!). These "paper costumes" were apparently just as widely varied as the more opulent and expensive garb of the wealthy. The magazine article lists, amongst other such costumes reported at recent events: Pierrot, Red Riding Hood, Japanese, Chinese, a Merveilleuse of the French Directoire period, marquis(e), clown, laundress, village bride, dirigibles, bi-planes, and various flowers, including a wonderful rose accompanied by a butterfly. Another novel idea to reduce expense was the “dîner à têtes”, or “dinner of heads” (admittedly not as elegant-sounding in English as in French). The idea was to costume yourself from the head up only, representing whatever historical era, person, or creative thing you wished, and otherwise wear normal evening dress, thus saving the cost of paying a dressmaker or tailor a fortune to create your costume vision. Here are some examples, from 1910. They are described as (1) Greek coiffure; (2) Louis XV bonnet; (3) Greek coiffure; (4) & (5) 'Directoire' caps (i.e. ca. 1790); (6) Louis XV coiffure; (7) Spanish headdress; (8) Greek coiffure. The extent to which these designs reflect historical costume, as opposed to Edwardian, is debatable. And some truly incredible "hats" or headdresses were intended to evoke various concepts: In an age before any radio or electronic entertainment, when people had to make their own fun, the 1910 magazine reports that hosts and hostesses tried to outdo their guests in creativity with "dîners surprises" (surprise dinners), where the table was set with large bowls of imitation fruits, vegetables, pastries, etc., all made in paper, meant to be donned by the guests as headdresses (see the two examples at top in the sketch above). Some of these dinners must have been lively affairs! The magazine mentions a "nose lit by a pocket battery" (who would have expected that such things existed in 1910!), as well as electric tie-clips. One supply house was reported as specializing in "exploding balls" and "surprise bombs", which were apparently designed to be thrown, and which, at the moment they exploded, released a rain of balloons, candy, and other party favours. Whether these were actual incendiary devices (like firecrackers), or whether they just broke open on impact isn't clear from the 1910 text. With the coming of WWI, feature articles covering these extravagant dress-up balls and their costumes disappeared from fashion journals, especially those published in France (it was hard to justify such frivolous and wasteful activities during wartime). But there are of course many stories of the costume ball being revived in the 1920’s – and with a passion! Although fancy dress balls and masquerades are still occasionally held today, it seems that fantasy costuming has moved to a different type of venue, the “this-and-that Con”, a conference (or is it conglomeration?) of people dressed as their favourite movie or fantasy characters, or else to Hallowe’en parties, where the dress-up sky is the limit. From a costume historian’s point of view, the question arises: should these garments of the Edwardian era be considered part of a study of costume history, or do they more appropriately belong to the area of theatrical costuming? My own view is that “fancy dress” or “fantasy dress”, as worn at gatherings in everyday life (i.e. not on the stage) is indeed part of costume history, albeit occupying a quirky corner, and is worthy of attention. What we can glean from these ensembles is how previous fashions were imagined and interpreted by makers of the particular time period, which can be interesting as a reflection of contemporary fashion trends. Additionally, some of the historical costumes intended for these balls were such elaborate and imaginative works of textile design in themselves, made in rich fabrics and highly ornamented, no less costly than fine evening gowns, and often made by the same designers. Their embellishment typified motifs and colours of contemporary design. I have to admit that I’m fascinated by these clever, creative confections – especially those of the Edwardian era. Few examples of these glorious costumes survive, although the MET (Metropolitan Museum of Art) does have a sampling from the late 1880’s to 1910’s, two of which are shown below. I’ve also seen the occasional “fancy dress” costume offered in private sales over the years, but it might be hard to claim that these weren’t actually theatrical costumes. Without specific provenance it’s difficult to be certain. Some fancy dress costumes of the late Victorian and the Edwardian period were made by the leading couturiers/couturières of the era for prominent socialites, and must have cost a small fortune to have custom-made. Yet even in these, it's possible to see the fashion "prejudices" of their day. Here for example, is a Worth gown in the MET collection, dated ca. 1893 that reflects elements of cut, structure, colour, and accessories that are contemporary to the late 1890's, but executed through an interpretation of an 18th century aesthetic: One example that I recently happened to come across (shown below) was sold by a private auction house some time ago. It is from 1911-12, made by Worth (as evidenced by a photo of the interior bodice petersham). It seems to me this was clearly a dress for a high society costume ball, evoking a beautiful butterfly. It is extravagantly custom-made, with extensive artistic embroidery on a couture level. It’s hard to imagine that so much fine embellishment work would have been lavished on a mere stage costume. What is interesting, at least from the standpoint of costume history, is that the gown itself, aside from all the creative embellishment, follows the typical, fashionable cut, structure, and silhouette of an evening gown of 1912. Ultimately, such flights of sartorial whimsy had little effect on contemporary fashion of the Edwardian period (if anything, the influence was in the reverse direction), yet from the perspective of costume history it is intriguing to study how such garments mirrored or followed the fashion modes and conventions of their day.

In this sense, these travestis were much like the majority of movie costumes of the modern era, which often say more about the fashion conventions of the time in which the movie was made than the fashion realities of a past era. Even movies made just 30 or 40 years after the subject date of a story rarely escape their own contemporary aesthetic. The next time you watch a 1940's movie intended to be set in an earlier age, see if you can identify the elements of contemporary style that make for historical fashion faux pas in the costumes -- they're almost always there. As for Edwardian fancy dress, aside from being a captivating study in fashion history, these wonderfully creative frivolities and the balls and dinners to which they were worn also say a great deal about social norms just before the world broke apart in 1914. For that reason alone, surviving examples are worth preservation and study.

4 Comments

10/1/2022 01:01:35 pm

It came in shoes first, then in bags and now it is stealing the hearts of the fairer gender in the form of jackets. Leather has always been a wonder material when it comes to making accessories. Besides the sturdiness of the material that is almost taken for granted, leather is also stealing the show with the variety of looks it is capable of showcasing.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPatricia Preston, a.k.a. The Fashion Archaeologist, Historian, linguist, pattern-maker, enthralled by historical fashion, especially the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.. Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed