|

In Part II in this series, I'll be looking at the 1760-65 era, with a focus on the dress depicted in Gainsborough's portrait of Lady Mary Howe, painted in about 1764, using replica garments based on those in the painting. I'll also discuss the connection of Lady Mary's husband, Richard Howe, to Canadian history of the time. Although most aspects of women's middle to upper middle class dress of the 1760's remained as they had been a decade before, there were subtle changes, which will be demonstrated in my talk. The presentation is planned to be held in Market Square in Annapolis Royal beginning at 2:00 pm on Saturday, August 27th, but as always, weather will determine if it can go ahead. The rain/alternate date will be Sunday, August 28th. For an overview of the typical elements of female dress of the mid-18th century, with photos of extant museum pieces and paintings, download the PDF document below.

If you're interested in details on my work making the replica of Lady Mary's ensemble, see the link below (the blog is in 4 parts):

0 Comments

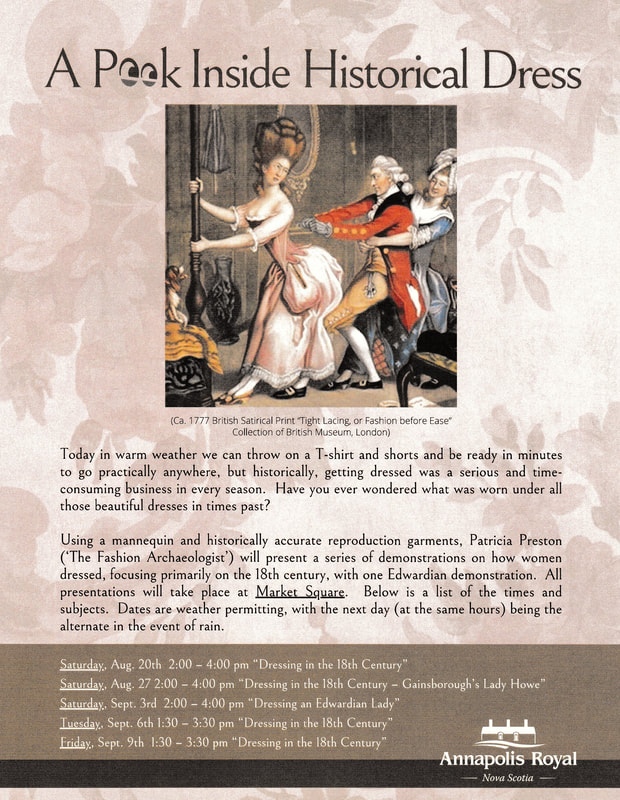

During August and early September this year (2022), as part of my historical interpretation work with the Town of Annapolis Royal, I'll be presenting a series of free talks on how women dressed in historical times. See the copy of the flyer below for details of dates and times. Part I, which takes place on Saturday, August 20th beginning at 2:00 p.m. in Market Square in Annapolis Royal, will be a demonstration, using historically accurate reproduction garments (on a mannequin), of the typical fancy dress of a British middle to upper-middle class lady, around 1750 to 1755. The PDF document below provides descriptions and examples of the elements of dress of the period which I'll be displaying and discussing. Download the PDF document for reference or -- if you have a mobile phone with you on which to download -- follow along if you are attending the talk. I hope to see you there!

Here is the flyer with the schedule for the entire series (some topics will be repeated later on).

Absorbing Surprises in Historical Costume (a.k.a. Fashions that shouldn't exist) As a fashion historian I always try to be aware of what I call “absolutism” when thinking about or discussing historical costume. One of the easiest and most enticing traps to fall into where historical dress is concerned (particularly for time periods prior to the mid-19th century) is making unconditional statements or conclusions based on what is necessarily a limited supply of evidence.

I've always believed that the further back in time one goes, the less justifiable it is to indulge in "fashion absolutism", i.e. rule-making. This is often proven true with the sudden appearance on the open market of an historical garment in a style or construction that "should not exist". Avoiding such difficulties is essentially a matter of seeing beyond what might ordinarily seem to be settled borders of history. Put another way, it means training the eye and mind to accept what is really there, sometimes without being able to fit an item neatly into a previous category. This is especially the case where the 18th century is concerned, in fact for any time prior to about 1860, when photography and mass-market print publications became widely available, giving us a more direct window into what people wore. The subject of lacing in 18th century garments came up in a costume-related online discussion recently, and I thought it was a little corner of costume history interesting enough to delve into in a bit more detail, with a few examples. In this particular discussion, lacing referred to either decorative (or sometimes functional) front lacing on garments, not the lacing closures in stays or other underclothing. There was a variety of lacing on bodices throughout the 18th century, as you might imagine, some of it quite cleverly executed (yes, "Varietie" in the title above is the archaic spelling, just for fun). Generally, but not always, this lacing, if intended to be seen, was done in a criss-cross pattern, in contrast to the spiral lacing typical of stays. I haven't yet found any definitive source(s) for exactly why this was the case, but in many extant garments (e.g. stomachers) where bodice front lacing can still be seen, the lacing is usually criss-crossed, sometimes with a little decorative loop in the middle. In terms of garment construction, I can think of four types of 18th century bodice front lacing -- at least as seen in the few surviving examples documented -- but there are probably more. I'm deliberately leaving out fabric bands, fancy bows (échelles), buckled bands, clasps, and the like (seen in many paintings of the era) that were also used to cross or close the front of bodices, and will be focusing rather on narrower lacing only, i.e. cord-like or fine ribbon lacing. I'm also ignoring jacket front closures, where lacing was likely more common.

Here then are the four types that spring to mind fairly spontaneously from my own recall and experience in research. This, I should point out, is not intended in any way as an exhaustive or conclusive treatment of the subject, but as a brief glimpse of this niche of historical fashion (click on "Read More" to continue): Although I work regularly with antique publications that include a plethora of information on both fashion and contemporary life, it's rare to come across a detailed description of an historical dance pre-dating the early 20th century. In this case, the dance in question is the 'Gavotte', a dance which had peasant origins in the 16th century, but was transformed into a "danse galante" that became popular -- and even prescribed -- in the court of Louis XIV. A while ago, while researching another subject altogether, I happened upon an incredibly precise, step-by-step explanation (complete with a sketch) of how the Gavotte was performed in the 18th century (the word "performed" here is more apt than simply "danced", as the description gives the impression of a series of moves that could only be executed by the most practised and skilled of couples). The Gavotte is difficult to define, as it changed a great deal in character from its humble country beginnings as a type of French bransle, to a more structured 17th century dance, to its formal, courtly manifestation in the 18th century. One common characteristic is the stepping, rather than sliding motion of the dance. Bach particularly liked this form of music, and wrote many Gavottes, as did Rameau and Lully for the court of Louis XIV. It continued to be danced (and composed by musicians) for decades afterward. I was so impressed by this unusual article that I decided to translate the entire text from the original French, along with some notes on the music itself, which I've posted below; I've also included the source French article for those who would like to read it in the original language. Some of the references are now a bit obscure, but I've tried to make sense of them within the context:

Later on, I happened across an 18th century colour version of a very similar sketch to the sketch that had been used in the Edwardian article (shown above) to illustrate one of the steps in this dance (it's possible it may have come from the same 18th century publication). I've posted the colour sketch at top. (Funny how you often find just what you need by coincidence once your mind is focused on it!). I like to imagine that whoever it was that wrote this article ca. 1905 had access to technical information that is more direct than what we have today, perhaps through one of the last of the old dance-masters of the 19th century still practising in the early 20th (maybe the Professor mentioned in the article?), who had the skills and knowledge handed down from the courts of the last French kings. By 1905 it had long disappeared from formal ballrooms. For those who may want even more specifics about the Gavotte, there is an extensive review of its musical features and history of the dance itself on Wikipedia here:

The following is a brief synopsis of my research paper, without illustrations. The full paper can be accessed, including supporting photos and plates, in PDF format -- click on the icon above to read or download the entire paper. The paper is the culmination of several months of study, investigation, research and writing, which I hope will add something useful to the understanding of historical costume of the period. What do well-fed cows, swords in their scabbards, fur-lined medieval gowns, hands stuffed into pockets, and nosy Parkers all have to do with certain 18th century garment names? No idea? Please read on!

At the risk of adding more verbiage to the discussion on the obscure subject of the 18th century word ‘fourreau’, I’m piling on my own thoughts – but from a completely new perspective, and to an extent not dealt with previously. I hope my research will help to illuminate this small corner of 18th century costume history. As a trained linguist and historian, and former professional translator (French/English), I had noticed some misunderstandings in publications and online discussions around the 18th century fashion term ‘fourreau’. I felt it might be useful to study the question in depth from the standpoint of linguistics, and to look at the entire history of the word in the context of costume history. Linguistics can be an illuminating resource in comprehending otherwise puzzling fashion nomenclature of earlier centuries in general, but in this case I believed it was an essential tool in untangling the confusion around the 18th century use of the intriguing fashion term ‘fourreau’. Considered along with careful scrutiny of contemporary 18th century fashion illustrations and texts, I felt linguistics could make the whole subject less mysterious. |

AuthorPatricia Preston, a.k.a. The Fashion Archaeologist, Historian, linguist, pattern-maker, enthralled by historical fashion, especially the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.. Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by Dot5Hosting

RSS Feed

RSS Feed