In Part II in this series, I'll be looking at the 1760-65 era, with a focus on the dress depicted in Gainsborough's portrait of Lady Mary Howe, painted in about 1764, using replica garments based on those in the painting. I'll also discuss the connection of Lady Mary's husband, Richard Howe, to Canadian history of the time.

Although most aspects of women's middle to upper middle class dress of the 1760's remained as they had been a decade before, there were subtle changes, which will be demonstrated in my talk.

The presentation is planned to be held in Market Square in Annapolis Royal beginning at 2:00 pm on Saturday, August 27th, but as always, weather will determine if it can go ahead. The rain/alternate date will be Sunday, August 28th.

For an overview of the typical elements of female dress of the mid-18th century, with photos of extant museum pieces and paintings, download the PDF document below.

| Elements of mid-18thC Dress.pdf |

If you're interested in details on my work making the replica of Lady Mary's ensemble, see the link below (the blog is in 4 parts):

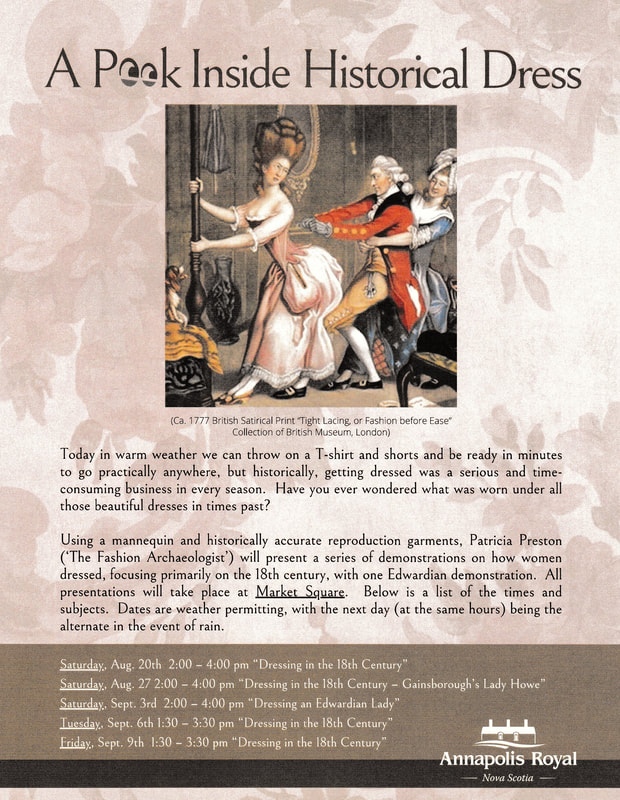

]]>During August and early September this year (2022), as part of my historical interpretation work with the Town of Annapolis Royal, I'll be presenting a series of free talks on how women dressed in historical times. See the copy of the flyer below for details of dates and times.

Part I, which takes place on Saturday, August 20th beginning at 2:00 p.m. in Market Square in Annapolis Royal, will be a demonstration, using historically accurate reproduction garments (on a mannequin), of the typical fancy dress of a British middle to upper-middle class lady, around 1750 to 1755.

Part I, which takes place on Saturday, August 20th beginning at 2:00 p.m. in Market Square in Annapolis Royal, will be a demonstration, using historically accurate reproduction garments (on a mannequin), of the typical fancy dress of a British middle to upper-middle class lady, around 1750 to 1755.

The PDF document below provides descriptions and examples of the elements of dress of the period which I'll be displaying and discussing. Download the PDF document for reference or -- if you have a mobile phone with you on which to download -- follow along if you are attending the talk.

I hope to see you there!

| NOTES-dressing_in_18thc-part_1.pdf |

Here is the flyer with the schedule for the entire series (some topics will be repeated later on).

]]>Well, today is already April 2nd, but did you play a practical joke on a friend yesterday, or become the victim of one yourself? I know, I know – with so many deeply worrying things going on in the world today, it’s hard to be serious about being silly.

Yet April Fool’s Day has a very old, albeit obscure, history that few people know about. There are various contested and contradictory theories of its origin, including disputed connections with Chaucer, the zodiacal shift marking the beginning of spring in temperate climates, the 16th century change to the modern (Gregorian) calendar, the opening of fishing season in certain regions, and the most obvious – the Catholic period of Lent (with its relationship to fish). Most people today simply take it for granted that April 1st is the day for playing pranks, without wondering why that is. But it has a fascinatingly mysterious and convoluted origin.

Yet April Fool’s Day has a very old, albeit obscure, history that few people know about. There are various contested and contradictory theories of its origin, including disputed connections with Chaucer, the zodiacal shift marking the beginning of spring in temperate climates, the 16th century change to the modern (Gregorian) calendar, the opening of fishing season in certain regions, and the most obvious – the Catholic period of Lent (with its relationship to fish). Most people today simply take it for granted that April 1st is the day for playing pranks, without wondering why that is. But it has a fascinatingly mysterious and convoluted origin.

There is documentation of such a day of pranks going back at least to the late 1600’s in England, but the English-speaking world isn’t alone in this tomfoolery, the day being marked by good-natured shenanigans in many countries. However, French history provides intriguing clues to the origin of the tradition of April 1st.

In France, “Poisson d’avril” (literally “April fish”) still marks the first day of April. Some French sources claim that this term can be traced to the mid-1400’s, a “poisson d’avril” being a young messenger boy or intermediary sent by his master with a letter to be delivered to his beloved, presumably in spring (April).

The next evidence of the phrase “poisson d’avril” in France is said to be in the 17th century, described later (around 1718) in the dictionary of the Academie Française as sending someone on a futile errand in order to make fun of them. This usage corresponds with the Scottish and Irish April 1st tradition of sending a person (the victim of the prank) with an ostensibly important letter to a recipient who is then directed by the letter to have the fool deliver it on to someone else, and so on, like a chain letter, until the fool finally discovers he’s been played.

The next evidence of the phrase “poisson d’avril” in France is said to be in the 17th century, described later (around 1718) in the dictionary of the Academie Française as sending someone on a futile errand in order to make fun of them. This usage corresponds with the Scottish and Irish April 1st tradition of sending a person (the victim of the prank) with an ostensibly important letter to a recipient who is then directed by the letter to have the fool deliver it on to someone else, and so on, like a chain letter, until the fool finally discovers he’s been played.

Enter the Fish...

At some point in the French tradition, fish – in one form or another -- actually came into the picture for April 1st. Some sources claim (perhaps more from reasonable theorizing than actual evidence) that this was because, after the Gregorian calendar was introduced in 1582, pranks were played on those who still clung to the old “new year” festivities connected with the Catholic time of Lent (and arrival of spring), which had traditionally taken place on or around April 1st.

When Pope Gregory XIII prescribed the new Gregorian calendar for all of Christendom in 1582, the “new year” was set at January 1st. The theory goes that, in order to mock those following the old traditions, people would pin a fake fish to the “fool’s” back, at the end of the Lent period (about April 1st).

When Pope Gregory XIII prescribed the new Gregorian calendar for all of Christendom in 1582, the “new year” was set at January 1st. The theory goes that, in order to mock those following the old traditions, people would pin a fake fish to the “fool’s” back, at the end of the Lent period (about April 1st).

Yet others say that evidence of the term “poisson d’avril” existed well prior to 1582, making the calendar-related origin an untenable explanation. They maintain that the tradition goes back to the opening of fishing season in many regions, with pranksters pinning real fish to the backs of either very successful (or unsuccessful) fishermen until of course the joke was discovered by the “fool” himself through the smell of the rotting fish. The trouble with this assumption is that historically, dates for opening the fishing season varied widely in Europe.

Another hypothesis claims that the April 1st tradition of pranks may have its antecedents in pagan rites of passage into spring (from the zodiac sign of Pisces – the fish -- into that of Aries), mixed with later Catholic traditions of Lent around early April, during which fish is the only permitted meat.

Whichever theory may be the true explanation of this phenomenon, the fact remains that it has persisted up to the present day. In France to this day, “Poisson d’avril” involves pinning a paper fish to another person’s back, or playing good-natured pranks or tricks on friends, associates, and relatives.

Another hypothesis claims that the April 1st tradition of pranks may have its antecedents in pagan rites of passage into spring (from the zodiac sign of Pisces – the fish -- into that of Aries), mixed with later Catholic traditions of Lent around early April, during which fish is the only permitted meat.

Whichever theory may be the true explanation of this phenomenon, the fact remains that it has persisted up to the present day. In France to this day, “Poisson d’avril” involves pinning a paper fish to another person’s back, or playing good-natured pranks or tricks on friends, associates, and relatives.

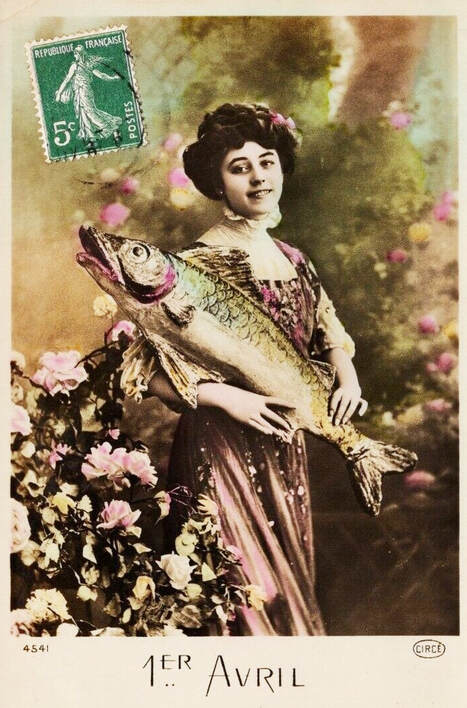

However, to go back a little in time to the early 20th century in France, through some mysterious social alchemy, the tradition of “Poisson d’avril” became mingled with what might be seen as a sort of ‘Valentine’s Day’ concept. Pretty, often hand-coloured cards, with a mixture of whimsy and gentle humour, sweetness and lover’s rhymes, were sent between sweethearts or good friends on April 1st.

These were extremely popular in France from about 1900 through to WWI, so much so that they are still ubiquitous in antique shops in France today. I’ve included some examples in this essay, taken from my own collection.

These were extremely popular in France from about 1900 through to WWI, so much so that they are still ubiquitous in antique shops in France today. I’ve included some examples in this essay, taken from my own collection.

These Edwardian “Poissons d’avril” cards combined the original 15th century concept of the intermediary messenger carrying his master’s “billet doux” along with the tradition of the April 1st fish – a sign of Lent and perhaps of plenty – often including a little prank (such as not revealing the name of the sender), to create a whimsical wish on April 1st for love, happiness, and good fortune.

For example, the card below, from ca.1900-05, sold at the time to be sent as a loving message from a French soldier to his sweetheart, might at first seem rather bizarre, even a bit ghoulish, without an understanding of the positive, sweetly jocular, and charming connotations of this tradition in France, including the religious meaning. The soldier is sending his love and wishes for happiness at Lenten time, as in the tradition of the 15th century origin of the April messenger of love, by way of his emissaries, the fish (which are also not coincidentally, directly connected with the Christian religious symbol).

The rhyme says (my translation) -- "Over the noise of the cannon my exiled heart/Sends you, along with my best wishes, some lovely April fish".

The rhyme says (my translation) -- "Over the noise of the cannon my exiled heart/Sends you, along with my best wishes, some lovely April fish".

Colourful flowers and ribbons often figured with the proffered fish on such cards. The fish itself was frequently the stand-in for the sender, as in this charming little card, the rhyme expressing a sentiment not unlike a Valentine’s Day card from a secret admirer: “Le nom du poisson, je dois le taire/ c’est un doux secret, c’est un mystère…” (“The name of the fish, I must not say/ ’tis a sweet secret, a mystery”).

As one typical example of these cards stated: “Poissons d’Avril portent Bonheur” (“April fish bring happiness”), the word « bonheur » meaning both happiness and good fortune (or good luck) in French, a little missive of love to a friend or sweetheart.

My special interest in these charming cards are the photographs (rather rare in themselves for the time period), mostly showing people in dressy but presumably typical garments and hairstyles of the day. This is an unintended, and therefore probably candid, look at Edwardian and 1910's fashion as it was worn, which adds another layer to the historical understanding of costume of the era.

Beyond this, the cards themselves are certainly little windows into the social mores and expectations of life over a hundred years ago in France, as reflected in the April 1st card below, ca.1904, which hints at the "very sweet things" she has entrusted to the fish she sends along to her sweetheart.

Beyond this, the cards themselves are certainly little windows into the social mores and expectations of life over a hundred years ago in France, as reflected in the April 1st card below, ca.1904, which hints at the "very sweet things" she has entrusted to the fish she sends along to her sweetheart.

Today in much of the world of course, we send pranks, rather than sweet cards, on April 1st, with public entities, media, and corporations getting in on the practical jokes. On this April 1st of 2022 the usual pranks seemed to be mostly absent, although understandably so, with both a pandemic and a brutal war constantly in the background. Few are in the mood for practical jokes and silly levity right now.

Yet with its history extending back centuries, this means of spreading laughter, fun, and mischievous friendship on one particular day of the year is surely worth perpetuating.

Whichever origin theory you may subscribe to, I hope April 1st brought you some smiles, happiness, and the hope of good fortune, with or without the pranks!

]]>Yet with its history extending back centuries, this means of spreading laughter, fun, and mischievous friendship on one particular day of the year is surely worth perpetuating.

Whichever origin theory you may subscribe to, I hope April 1st brought you some smiles, happiness, and the hope of good fortune, with or without the pranks!

(a.k.a. Fashions that shouldn't exist)

As a fashion historian I always try to be aware of what I call “absolutism” when thinking about or discussing historical costume. One of the easiest and most enticing traps to fall into where historical dress is concerned (particularly for time periods prior to the mid-19th century) is making unconditional statements or conclusions based on what is necessarily a limited supply of evidence.

I've always believed that the further back in time one goes, the less justifiable it is to indulge in "fashion absolutism", i.e. rule-making. This is often proven true with the sudden appearance on the open market of an historical garment in a style or construction that "should not exist".

Avoiding such difficulties is essentially a matter of seeing beyond what might ordinarily seem to be settled borders of history. Put another way, it means training the eye and mind to accept what is really there, sometimes without being able to fit an item neatly into a previous category.

This is especially the case where the 18th century is concerned, in fact for any time prior to about 1860, when photography and mass-market print publications became widely available, giving us a more direct window into what people wore.

I've always believed that the further back in time one goes, the less justifiable it is to indulge in "fashion absolutism", i.e. rule-making. This is often proven true with the sudden appearance on the open market of an historical garment in a style or construction that "should not exist".

Avoiding such difficulties is essentially a matter of seeing beyond what might ordinarily seem to be settled borders of history. Put another way, it means training the eye and mind to accept what is really there, sometimes without being able to fit an item neatly into a previous category.

This is especially the case where the 18th century is concerned, in fact for any time prior to about 1860, when photography and mass-market print publications became widely available, giving us a more direct window into what people wore.

As I've mentioned in other articles I've posted on this site, I find that it's typically the privately listed historical garments that get the most thorough photographic attention, and as such are far more helpful to a costume historian than many museum photographs are (personal viewing of extant garments aside).

The photograph below (from a private online auction listing), which gives a rare view of the interior construction of the bodice of a ca. 1770-75 gown in a silk/cotton striped textile, is a good example. In fact, often even the descriptions of privately sold garments are more detailed than those given by museums for similar garments. From the photograph below it's possible to see and study quite a number of period construction techniques which can inform further study or the making of reproduction garments.

The photograph below (from a private online auction listing), which gives a rare view of the interior construction of the bodice of a ca. 1770-75 gown in a silk/cotton striped textile, is a good example. In fact, often even the descriptions of privately sold garments are more detailed than those given by museums for similar garments. From the photograph below it's possible to see and study quite a number of period construction techniques which can inform further study or the making of reproduction garments.

Privately owned or listed antique garments that come on the market can accordingly be very illuminating -- even surprising -- in their variety and detail, sometimes to the point of proving that what experts think was "likely not seen" in a particular era did indeed exist. If nothing else, they frequently provide a glimpse into what sort of clothing was worn by people who were not in the upper class, in other words, the average person's dress. These are quite often garments that come out of everyday middle-class estates, tucked away for decades in a dark trunk in someone's attic by an unrecorded ancestor before being brought up for auction.

I would define “historical absolutism” generally (that is, not specifically where costume history is concerned) as a tendency to make definitive, final, or rather permanent statements or conclusions about some aspect of history based on what is necessarily a rather small sampling. This is particularly a pitfall where 18th century fashion is concerned, since study is frequently limited perforce to just a handful or two of surviving examples or paintings.

I think it’s a natural human desire (or at least a natural modern one), to want to categorize, classify, label, and pigeon-hole new things once we’ve already seen a few that appear to conform to a type. The file then gets closed and put away as case solved, with little inclination to revisit the matter. The natural tendency is to ignore or dismiss as odd – if not impossible – any item or information that subsequently appears which doesn’t fit the established parameters. This is indeed I think the definition of a mental trap.

I think it’s a natural human desire (or at least a natural modern one), to want to categorize, classify, label, and pigeon-hole new things once we’ve already seen a few that appear to conform to a type. The file then gets closed and put away as case solved, with little inclination to revisit the matter. The natural tendency is to ignore or dismiss as odd – if not impossible – any item or information that subsequently appears which doesn’t fit the established parameters. This is indeed I think the definition of a mental trap.

In fairness I must add that many reputable costume historians are careful to use qualifiers and circumscription when describing their findings, allowing them to revisit, modify and revise earlier conclusions when new evidence comes to light. This is a more rational and even scientific method than closing the door permanently on a particular subject and stashing it away as complete and resolved.

Put simply, where costume history in particular is concerned, one garment (or even a handful of garments) does not always a fashion rule make!

I so often see online comments stating: “this-or-that was not done or seen”, or “such-and-such wasn’t worn or didn’t exist”, sometimes even with “never” or “always” added, which only magnifies the problem. Yet the truth is (and I believe most professional historians would agree), the further back in time we go, the less we can be certain of any definitive, final statement about history and historical dress.

So what feeds into this compulsion to “close the case”, and how can it be avoided, particularly by amateur enthusiasts of the subject?

One important factor that I believe tends to encourage “historical absolutism” is a failure to recognize how narrow and uneven a slice of contemporary fashion we have in extant 18th century garments, particularly those held by world museums.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that our understanding of historical dress based on extant 18th century garments themselves can be skewed due to the limited number of surviving pieces (largely in museum collections) and the reasons for which they survived. Both museum selection criteria and – long before items reach museums – personal motives for retaining and preserving particular garments, colour our view of 18th century fashion.

Museums tend to purchase “important” pieces representing a time period and the height of design or embellishment. These rare and beautiful pieces are often selected because they are in good (or excellent) condition for display and longevity purposes.

Put simply, where costume history in particular is concerned, one garment (or even a handful of garments) does not always a fashion rule make!

I so often see online comments stating: “this-or-that was not done or seen”, or “such-and-such wasn’t worn or didn’t exist”, sometimes even with “never” or “always” added, which only magnifies the problem. Yet the truth is (and I believe most professional historians would agree), the further back in time we go, the less we can be certain of any definitive, final statement about history and historical dress.

So what feeds into this compulsion to “close the case”, and how can it be avoided, particularly by amateur enthusiasts of the subject?

One important factor that I believe tends to encourage “historical absolutism” is a failure to recognize how narrow and uneven a slice of contemporary fashion we have in extant 18th century garments, particularly those held by world museums.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that our understanding of historical dress based on extant 18th century garments themselves can be skewed due to the limited number of surviving pieces (largely in museum collections) and the reasons for which they survived. Both museum selection criteria and – long before items reach museums – personal motives for retaining and preserving particular garments, colour our view of 18th century fashion.

Museums tend to purchase “important” pieces representing a time period and the height of design or embellishment. These rare and beautiful pieces are often selected because they are in good (or excellent) condition for display and longevity purposes.

These are certainly magnificent garments, often amazingly well preserved, and without a doubt worthy of attention and study. Most originated with wealthy, prominent or aristocratic families, not generally representative of middling or lower class dress.

As a whole, such collections depict a small segment of 18th century society. In this respect, such gowns are not unlike most of the beautiful garments captured in 18th century upper class portraiture. From our viewpoint, it's like looking through a narrow slit at a large painting and trying to understand the entire picture. Not only are such collections often weighted toward the higher class of dress, but museums do occasionally get the dating, or the mounting and display of a costume wrong, which can further add to erroneous conclusions by viewers.

It’s also important that every piece of historical clothing be situated in an understanding of its original geographical and social context, which means researching a broader field in order to judge how typical a garment was for its time and place.

It’s also important that every piece of historical clothing be situated in an understanding of its original geographical and social context, which means researching a broader field in order to judge how typical a garment was for its time and place.

Regional differences in dress (and other areas of life) were more pronounced in the 18th century than they are today in our era of mass-media and frequent travel. A style worn in a portrait in ca.1750 southern France for example, might be quite out of place and even unknown (that is, not worn), in England at the same date.

It’s essential to be able to recognize when these factors apply to any historical garment. One example follows, a ca.1703 painting entitled La Belle Strasbourgeoise byNicolas de Largillière, although many more exist. Before deducing anything from this portrait in relation to conventional European dress of 1703, a thorough investigation of the history and costume of the Strasbourg region would need to be done. You would discover for example that this area passed from one European power to the other (mostly French and German) for centuries and was influenced by both. Deeper research would no doubt reveal further information about the costume shown in this fascinating image:

It’s essential to be able to recognize when these factors apply to any historical garment. One example follows, a ca.1703 painting entitled La Belle Strasbourgeoise byNicolas de Largillière, although many more exist. Before deducing anything from this portrait in relation to conventional European dress of 1703, a thorough investigation of the history and costume of the Strasbourg region would need to be done. You would discover for example that this area passed from one European power to the other (mostly French and German) for centuries and was influenced by both. Deeper research would no doubt reveal further information about the costume shown in this fascinating image:

Here is another example, a ca. 1745-50 painting entitled “Portrait of a Jacobite Lady” (byCosmo Alexander). Any conclusions about this lady’s style of costume vis-à-vis typical English costume would need to involve research into the history of Scottish dress of the middle to upper classes of the period (few people of the lower classes could afford to commission a formal portrait). A proper consideration of this costume would likely also require research into military dress of the period.

Further, the dress of ordinary folk (i.e. those above the poor, but below the wealthy) are generally not well represented in terms of their proportion to finer clothing in museum collections, or indeed in paintings. Part of this is likely because “ordinary” costume was not as worthy of careful preservation, and was simply discarded or used for other purposes once worn out or hopelessly unfashionable, leaving fewer surviving examples. For these types of clothing, we really only have the occasional glimpse provided by artists who depicted “everyday” life, or by the often tangential evidence of written documentation.

Another factor compounding the issue of how to think about historical dress is what is sometimes called “preservation bias”. I don’t particularly like this term because it suggests that the bias exists around what is preserved or why, in other words a bias at the origin point, rather than a bias in our thinking about and observing preserved garments.

Bias at the origin point may sometimes certainly be a factor (the owner liked blue better than green, long better than short), but it’s not the whole story. Happenstance, fate, and whimsy can often play just as important a role in whether a particular garment is carefully saved by the original owner, and later by their descendants or others. We should acknowledge that sometimes garments are put away and saved because they were unusual, or because they represented a particular moment in an owner’s life, or – more prosaically – because they were simply forgotten, not necessarily because they were a typical example of contemporary fashion.

All of this is not to say that we can’t reach some broad, generalized conclusions about fashion and style in a given time period and place. But these always need to be tempered by a recognition of the often limited number of pieces available for study, and qualified in terms of exceptions to what seem “typical” costume of the era. In short, qualifying terms such as “more” or “less”, “generally”, “frequently” or “rarely”, “likely” or “unlikely”, “usually” or “unusually”, and so on, are more appropriate to any discussion of historical dress than words like “never”, “not”, or “always”.

Bias at the origin point may sometimes certainly be a factor (the owner liked blue better than green, long better than short), but it’s not the whole story. Happenstance, fate, and whimsy can often play just as important a role in whether a particular garment is carefully saved by the original owner, and later by their descendants or others. We should acknowledge that sometimes garments are put away and saved because they were unusual, or because they represented a particular moment in an owner’s life, or – more prosaically – because they were simply forgotten, not necessarily because they were a typical example of contemporary fashion.

All of this is not to say that we can’t reach some broad, generalized conclusions about fashion and style in a given time period and place. But these always need to be tempered by a recognition of the often limited number of pieces available for study, and qualified in terms of exceptions to what seem “typical” costume of the era. In short, qualifying terms such as “more” or “less”, “generally”, “frequently” or “rarely”, “likely” or “unlikely”, “usually” or “unusually”, and so on, are more appropriate to any discussion of historical dress than words like “never”, “not”, or “always”.

Lastly, avoiding historical absolutism means having a willingness to fit a new discovery into an established picture of 18th century clothing. I’m always struck – and fascinated – by the occasional item from the 1700’s that surfaces in private sales or auctions. These items frequently “break the mould” of what we may think we know about fashionable clothing in the 18th century. They cause us to look with fresh eyes and should remind us to think twice about making “never” or “always” statements about historical dress.

A few examples follow which illustrate the sort of items that might prompt a rethinking of some commonly held views of costume history, in these cases of the 18th century. Whether such items were high fashion, made by professional tailors or gown makers, or else home-made garments, really matters very little. Someone felt they were appropriate and/or fashionable to wear in their place and time.

A recent example that interested me were these 18th century European velvet stays, listed on an online retail selling platform. This garment is unusual in several ways, certainly not typical, yet there it is, forcing us to bend our view of fashion conventions of the 18th century just a little…

A few examples follow which illustrate the sort of items that might prompt a rethinking of some commonly held views of costume history, in these cases of the 18th century. Whether such items were high fashion, made by professional tailors or gown makers, or else home-made garments, really matters very little. Someone felt they were appropriate and/or fashionable to wear in their place and time.

A recent example that interested me were these 18th century European velvet stays, listed on an online retail selling platform. This garment is unusual in several ways, certainly not typical, yet there it is, forcing us to bend our view of fashion conventions of the 18th century just a little…

Here is another instance of a surprising item in private hands, a man’s ca. 1770-75 suit (from the famous Tasha Tudor collection, most of which was sold at auction a few years ago). The unusual aspect here is not the cut of the suit, but the textile from which it was made, described as printed velvet, a textile I had not noticed in men’s 18th century suits before. (Following this full-length photo is a cropped version that gives a better view of the surface of the velvet itself.)

And another example: a spectacular, fully quilted sacque gown (robe à la française), ca.1750-60, from the collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute. It might be hard to imagine that such a complex garment requiring such skill in execution, completely quilted, yet made closely along the lines of contemporary silk gowns, could exist had this extant not survived.

Another styling that appears to break the usual 18th century rules is shown in the lovely ca.1750 portrait of the Marquise de Caumont La Force below, by Drouais. We’re accustomed to seeing fur trim on pelisses and cloaks, but surely fur trim on a gown, not to mention the addition of odd-looking lace sleeves, could not be right! It looks to be a very odd costume. And yet, the Marquise apparently wore it (and liked it well enough to have her portrait painted in it):

You might be tempted to say that the previous painting was surely a one-off oddity of personal taste (and therefore easily dismissed) but further research reveals that might not be the case. This is where established “rules” of 18th century dress and a tendency to lean towards finality (i.e. absolutism) can become a hindrance to a broader understanding of period costume.

Once you find an aberration, it’s important to research around the edges, so to speak, to see if that particular feature of style can be found elsewhere or in a similar form. In this case in fact, it seems this mode was not unique, for here is the Marquise de Pompadour herself, from about the same period in France, with fur trim on her gown (collection of the Musée du Louvre):

Once you find an aberration, it’s important to research around the edges, so to speak, to see if that particular feature of style can be found elsewhere or in a similar form. In this case in fact, it seems this mode was not unique, for here is the Marquise de Pompadour herself, from about the same period in France, with fur trim on her gown (collection of the Musée du Louvre):

The use of fur trim rather than ruching, furbelows or lace, also appears later, ca.1780-85, in a portrait of Marie-Antoinette (by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun). Interestingly, this is not the only portrait of Marie-Antoinette wearing a gown with fur trim:

You might be inclined to conclude, based on the above portraits, that this fashion of using fur to trim gowns was only a French idea. But it’s worthwhile to keep an open mind and a sharp eye to look further, for here is a portrait of Lady Holland, ca. 1765, by Allan Ramsay. Notice that even the flounces are trimmed with fur.

Having seen the above images, it’s hard to be completely confident making statements about what and wasn’t usually employed as trim on 18th century gowns. Whether the ca. 1770 portrait below (of the Maréchale de Bellisle, by Quentin de la Tour), depicts fur or feather trim on this sacque gown is hard to determine – it’s certainly one or the other.

Notice that the bodice also has the short sleeve tops and tiered lace sleeve flounces like those seen in the Drouais portrait above. While these styles may not fit into our typical expectations of mid- to late 18th century dress, they clearly existed, and merit study of their historical context. Doing so might result in a revision of our belief of what was fashionable or typical in 18th century upper class French dress. For the time being however, these paintings can remind us to keep an open mind.

Notice that the bodice also has the short sleeve tops and tiered lace sleeve flounces like those seen in the Drouais portrait above. While these styles may not fit into our typical expectations of mid- to late 18th century dress, they clearly existed, and merit study of their historical context. Doing so might result in a revision of our belief of what was fashionable or typical in 18th century upper class French dress. For the time being however, these paintings can remind us to keep an open mind.

I think that whenever one unusual garment is found, we should be willing to admit the possibility that there might have been others, rather than dismissing the unusual item off-hand as freakish, atypical or wrong.

Still, it’s true that placing such garments in a proper historical and social context can be a challenge. For example, understanding whether the French gowns shown in these portraits were strictly gowns donned for formal portraits or court attendances, or whether they were worn for normal dressy events such as dinners, receptions, visits, etc., would take much more specific research.

Still, it’s true that placing such garments in a proper historical and social context can be a challenge. For example, understanding whether the French gowns shown in these portraits were strictly gowns donned for formal portraits or court attendances, or whether they were worn for normal dressy events such as dinners, receptions, visits, etc., would take much more specific research.

This ca.1750-70 completely feather-covered bergère-style hat, in the V&A (Victoria & Albert Museum) collection provides another example of teaching the mind to see beyond the usual conventions of costume history. This may at first seem like an impossibly odd or unique variation on hats of the era. Was it perhaps even someone’s unique and weirdly aberrant idea of personal style?

However in fact another amazingly similar chapeau from the era exists in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which you might not know about without digging a little deeper on the subject:

A little further research turns up a depiction of what appears to be just such a feathered hat in this ca.1745 painting by Philip Mercier entitled “The School for Girls”. So now we have at least three examples, and it’s impossible not to admit that there could have been others at the time. Accordingly, we might need to revise our views on the materials and embellishments used on mid-18th century ladies’ hats.

Conventional wisdom on 18th century hat styles is that straw “bergère” hats with pretty ribbons and sparse trimmings were the height of style, but it’s quite possible that these feathered hats were just as fashionable and typical. Before concluding that they are bizarre anomalies, we need to consider the possibility that there simply weren’t enough of them that survived in proportion to straw hats.

The moral of this lesson? Be careful about jumping to conclusions where historical costume, especially before the mid-19th century, is concerned.

Conventional wisdom on 18th century hat styles is that straw “bergère” hats with pretty ribbons and sparse trimmings were the height of style, but it’s quite possible that these feathered hats were just as fashionable and typical. Before concluding that they are bizarre anomalies, we need to consider the possibility that there simply weren’t enough of them that survived in proportion to straw hats.

The moral of this lesson? Be careful about jumping to conclusions where historical costume, especially before the mid-19th century, is concerned.

I think by now you may see where I’m going with this: if we draw immutable, permanent lines around what we believe we know, we’re unlikely to be able to absorb and admit new information into our overall picture of historical fashion. In other words, it’s important to keep an open mind and be willing to drop old concepts once new examples appear, even if they don’t fit the expected types of an era.

I also believe it’s useful to bear in mind that people may have applied their own personal interpretation to contemporary fashion, while still remaining within the boundaries of what was acceptable at the time. I don’t think the 21st century has a monopoly on creative dressing.

I also believe it’s useful to bear in mind that people may have applied their own personal interpretation to contemporary fashion, while still remaining within the boundaries of what was acceptable at the time. I don’t think the 21st century has a monopoly on creative dressing.

Next is a rather subtle example of personal taste combining styles of different periods (certainly not the only one I’ve encountered though!). This is a robe à la française of ca.1755 (privately sold), with a very up-to-date compère (false vest) front of the type seen in other gowns and portraits of the period, yet with the older exaggerated “manches à la raquette” (racket-shaped cuffs). The gown was listed as being unaltered from its original state.

It seems that the original owner decided she would like a slightly older style of cuff on her gown, along with the new compère style. I’ve reproduced this gown myself (see details in my website Blog), mainly because I found this personal mix of newer and older so interesting. The wide, “tennis-racket” shaped cuffs can clearly be seen in the photos from the original sale listing, and in my reproduction of the gown:

It seems that the original owner decided she would like a slightly older style of cuff on her gown, along with the new compère style. I’ve reproduced this gown myself (see details in my website Blog), mainly because I found this personal mix of newer and older so interesting. The wide, “tennis-racket” shaped cuffs can clearly be seen in the photos from the original sale listing, and in my reproduction of the gown:

Another horizon-expanding example of 18th century dress is the ca. 1730-1750 embroidered linen robe à l’anglaise shown below, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Conventional historical costume wisdom would suggest that mid-18th century floral-sprigged gowns could only be made of silk brocade, in which case this gown would represent an oddity, perhaps to be dismissed within the usual boundaries of 18th century fashion – someone’s home project perhaps? The fact that extant gowns of this type may be very rare in collections today doesn’t prove that they weren’t both fashionable and possibly even more common than we might imagine – we simply may never really know. To continue the earlier metaphor, this file should remain open.

Conventional historical costume wisdom would suggest that mid-18th century floral-sprigged gowns could only be made of silk brocade, in which case this gown would represent an oddity, perhaps to be dismissed within the usual boundaries of 18th century fashion – someone’s home project perhaps? The fact that extant gowns of this type may be very rare in collections today doesn’t prove that they weren’t both fashionable and possibly even more common than we might imagine – we simply may never really know. To continue the earlier metaphor, this file should remain open.

A further example of an embroidered linen gown (from a later period), is shown below, from the LACMA (L.A. County Museum of Art) collection, dated ca.1760. This time the embroidery is executed in wool (see close-up photo).

Now we begin to wonder, given these two examples from completely different decades, how rare embroidered linen gowns really were. Or, we can ponder, if they weren’t rare or bizarre at all, was it only an accident of fate that so few were preserved? We can also leave open the possibility that these garments may have actually been made (i.e. re-purposed) from embroidered draperies, etc., rather than originally embroidered as gowns.

Now we begin to wonder, given these two examples from completely different decades, how rare embroidered linen gowns really were. Or, we can ponder, if they weren’t rare or bizarre at all, was it only an accident of fate that so few were preserved? We can also leave open the possibility that these garments may have actually been made (i.e. re-purposed) from embroidered draperies, etc., rather than originally embroidered as gowns.

The example below seems even more unusual and interesting, a ca. 1770-80 robe à la française made in a cotton textile referred to as “Indienne” (from its origin in India), with striking conifer tree motifs embroidered in wool. This was offered at private auction some years ago. This gown certainly fits the description of a garment that “shouldn’t exist”, but we’re forced by its presence, to absorb it into our overall view of 18th century fashion.

One possible theory is that the textile used in this gown (perhaps like the previous two gowns) may have begun its life as decorative drapery, bed hangings, bed coverings, or other soft furnishing. The gown is a wonderful example of the kind of surprising and unusual items that can pop up in private collections or sales. They may or may not have been widespread or typical at the time, but we simply can’t conclude they were rare based only on the fact that few survive today.

Once again, without further evidence (the likelihood of which is slim) it must remain an open-ended, unresolved case. All that can be said is that embroidered linen and India cotton gowns existed, but to what extent they were commonly made and worn at the time may never be known.

It’s also possible, if we’re thinking “outside the box”, that embroidered gowns such as these might have been too useful as sources of home decoration not to be turned back into draperies or other furnishings in much later eras, which would be one plausible explanation for the scarcity of surviving examples.

One possible theory is that the textile used in this gown (perhaps like the previous two gowns) may have begun its life as decorative drapery, bed hangings, bed coverings, or other soft furnishing. The gown is a wonderful example of the kind of surprising and unusual items that can pop up in private collections or sales. They may or may not have been widespread or typical at the time, but we simply can’t conclude they were rare based only on the fact that few survive today.

Once again, without further evidence (the likelihood of which is slim) it must remain an open-ended, unresolved case. All that can be said is that embroidered linen and India cotton gowns existed, but to what extent they were commonly made and worn at the time may never be known.

It’s also possible, if we’re thinking “outside the box”, that embroidered gowns such as these might have been too useful as sources of home decoration not to be turned back into draperies or other furnishings in much later eras, which would be one plausible explanation for the scarcity of surviving examples.

Lastly, there is the question of drawing conclusions about historical dress from contemporary paintings and sketches. Here I think the pitfalls are numerous. It requires a knowledgeable eye to sort out what is reality, fantasy, or artistic licence in 18th century art.

This is a subject worthy of deeper consideration which I plan to address in a separate essay as Part 2 in this series. Suffice it to say that not everything depicted in 18th century paintings accurately represented 18th century fashion for the average middle-class or even upper middle-class person.

One case in point is the loosely arranged, classically inspired drapery in this ca.1772 portrait of Ann Verelst, by George Romney. This has very little connection with contemporary dress of the period:

This is a subject worthy of deeper consideration which I plan to address in a separate essay as Part 2 in this series. Suffice it to say that not everything depicted in 18th century paintings accurately represented 18th century fashion for the average middle-class or even upper middle-class person.

One case in point is the loosely arranged, classically inspired drapery in this ca.1772 portrait of Ann Verelst, by George Romney. This has very little connection with contemporary dress of the period:

Still, there is one incontrovertible truth about costume history: If a surviving item is found, then obviously it existed in its time. Provenance is important and fascinating, but mostly in the context of the particular garment. What one surviving extant can’t tell us however, without at least a few other similar examples or contemporary documentation, is whether that garment was common and/or considered fashionable.

Certainly there are general themes and lines of fashion seen across numerous examples of surviving garments that are reasonable to deduce or hard to dismiss. Such things as the usual cut of gown sleeves along the horizontal pattern of a textile, the relative consistency of the shape and silhouette of the robe à la française through several decades, and the emergence of cotton textiles supplanting silk in the last quarter of the century, are examples of elements that are repeated widely enough in extant examples to provide some generally reliable outlines of 18th century fashion.

However, if we keep an open mind, then previously unseen examples of 18th century dress can help to crack open our fixed (and sometimes misguided) concepts regarding historical costume. Such “anomalies” can also suggest that personal style preferences may have been more important than we will ever know.

Accordingly, I think it’s with a certain arrogance that we claim that a particular mode of fashion could (or could not) have been done. That would presume that 18th century people (especially those with at least moderate economic status) were much less able to be creative in their dress than we are today. I find this premise hard to accept, which is why I believe a certain amount of freedom in reproducing 18th century dress, i.e. painting outside some of the lines, is more reasonable than we usually like to admit.

Certainly there are general themes and lines of fashion seen across numerous examples of surviving garments that are reasonable to deduce or hard to dismiss. Such things as the usual cut of gown sleeves along the horizontal pattern of a textile, the relative consistency of the shape and silhouette of the robe à la française through several decades, and the emergence of cotton textiles supplanting silk in the last quarter of the century, are examples of elements that are repeated widely enough in extant examples to provide some generally reliable outlines of 18th century fashion.

However, if we keep an open mind, then previously unseen examples of 18th century dress can help to crack open our fixed (and sometimes misguided) concepts regarding historical costume. Such “anomalies” can also suggest that personal style preferences may have been more important than we will ever know.

Accordingly, I think it’s with a certain arrogance that we claim that a particular mode of fashion could (or could not) have been done. That would presume that 18th century people (especially those with at least moderate economic status) were much less able to be creative in their dress than we are today. I find this premise hard to accept, which is why I believe a certain amount of freedom in reproducing 18th century dress, i.e. painting outside some of the lines, is more reasonable than we usually like to admit.

This is why first-hand historical accounts and observations on fashion, as rare as they are, can be so critical, filling in and adding to the picture of fashion of a particular era. Such accounts frequently occur as mere incidental (even oblique) notes by an observer in a completely unrelated text, diary or journal, but are precious as an on-the-spot window onto a lost world.

Some writers are better known for their skill and interest in observing such things, despite the likelihood that most had no awareness whatsoever of how incredibly valuable their few words on a contemporary fashion subject could be more than two centuries later!

I like to keep my eyes open for such little treasures when reading first-person accounts or works on history that describe a scene which may include comments about fashions. If a person who actually lived at the time gives opinions on what was worn and considered acceptable fashion, we have to treat those opinions as some of the truest representations we have.

Some writers are better known for their skill and interest in observing such things, despite the likelihood that most had no awareness whatsoever of how incredibly valuable their few words on a contemporary fashion subject could be more than two centuries later!

I like to keep my eyes open for such little treasures when reading first-person accounts or works on history that describe a scene which may include comments about fashions. If a person who actually lived at the time gives opinions on what was worn and considered acceptable fashion, we have to treat those opinions as some of the truest representations we have.

I offer one further example of a garment that “breaks the mould” of conventional wisdom about 18th century fashion (at least at the beginning of the 3rd quarter of the century in France). During the course of some recent research, I came across what at first seemed a typical illustration of 18th century fashion, from the “Galerie des Modes” of 1778. This fashion sketch or trade illustration shows a tailor/costumier fitting stays on a young lady, apparently a rather ordinary subject depicting a tailor in the course of his usual work.

At first I studied the illustration itself, which seemed to offer little beyond what I’d seen in other similar period sketches. What made this image interesting however, and what caught my attention, is that the brief description underneath mentions the stays are “covered in yellow coloured batiste”.

Although silk can be made in a batiste weave, it's more likely that "batiste" referred to a fine linen (or possibly cotton) at this era. The word "batiste" is said to have originated in the 1400's, and is defined by my etymological French dictionary (Le Robert) as "toile de lin très fine", meaning a very fine (i.e. lightweight and finely woven) linen cloth.

Summer stays covered with (cotton) batiste are a familiar Edwardian mode, but rarely considered in the context of the 18th century, where we tend to think of substantial linens being most suitable for hard-wearing stays. Batiste -- especially fine linen -- may have been a good choice for warm weather or summer wear.

Another explanation might be that linen or cotton batiste, still rather luxury fabrics at this time period, may have had a certain cachet for the most fashionable women whose stays would not expect to get frequent or heavy wear. It's also plausible that the tailor who posed for this illustration was merely keen to show off his most fashionable novelty.

Unfortunately for us, the printer of this illustration makes no mention of why such a fine textile was used. The textual description that accompanies the illustration in the "Galerie des Modes" sheds no helpful light on the particularities of the textiles used, aside from briefly describing the general construction of the stays.

At first I studied the illustration itself, which seemed to offer little beyond what I’d seen in other similar period sketches. What made this image interesting however, and what caught my attention, is that the brief description underneath mentions the stays are “covered in yellow coloured batiste”.

Although silk can be made in a batiste weave, it's more likely that "batiste" referred to a fine linen (or possibly cotton) at this era. The word "batiste" is said to have originated in the 1400's, and is defined by my etymological French dictionary (Le Robert) as "toile de lin très fine", meaning a very fine (i.e. lightweight and finely woven) linen cloth.

Summer stays covered with (cotton) batiste are a familiar Edwardian mode, but rarely considered in the context of the 18th century, where we tend to think of substantial linens being most suitable for hard-wearing stays. Batiste -- especially fine linen -- may have been a good choice for warm weather or summer wear.

Another explanation might be that linen or cotton batiste, still rather luxury fabrics at this time period, may have had a certain cachet for the most fashionable women whose stays would not expect to get frequent or heavy wear. It's also plausible that the tailor who posed for this illustration was merely keen to show off his most fashionable novelty.

Unfortunately for us, the printer of this illustration makes no mention of why such a fine textile was used. The textual description that accompanies the illustration in the "Galerie des Modes" sheds no helpful light on the particularities of the textiles used, aside from briefly describing the general construction of the stays.

The illustration makes it clear (from our vantage point) that such a garment was not unheard of, and possibly not unusual. It’s demonstrated in the sketch as in the normal course of a tailor’s usual work.

Nothing is said about the fine batiste covering being odd, bizarre, or new. Of course, the lack of commentary on this point doesn’t prove that linen batiste-covered stays were common, although the stays are shown on a fashionable-looking young lady with a very stylishly arranged coiffure. Take into account as well the fact that the title describes the garment as “Cor à la mode” (fashionable stays). Notable too is the fact that these are back-lacing stays with the addition of decorative front lacing, a fashionable touch.

The text focuses (unfortunately) on the tailor’s own costume, but provides a second interesting insight, mentioning that his waistcoat is made of “tricot”, i.e. apparently some type of knitted material. Presumably a tailor would be a well-dressed fellow in the latest style, to properly represent his profession. Note too that he is wearing velvet breeches and is shown with a fine lacy jabot at his neck.

Nothing is said about the fine batiste covering being odd, bizarre, or new. Of course, the lack of commentary on this point doesn’t prove that linen batiste-covered stays were common, although the stays are shown on a fashionable-looking young lady with a very stylishly arranged coiffure. Take into account as well the fact that the title describes the garment as “Cor à la mode” (fashionable stays). Notable too is the fact that these are back-lacing stays with the addition of decorative front lacing, a fashionable touch.

The text focuses (unfortunately) on the tailor’s own costume, but provides a second interesting insight, mentioning that his waistcoat is made of “tricot”, i.e. apparently some type of knitted material. Presumably a tailor would be a well-dressed fellow in the latest style, to properly represent his profession. Note too that he is wearing velvet breeches and is shown with a fine lacy jabot at his neck.

Following is my translation of the text shown under the illustration (I am a former professional French/English translator, and the notations in square brackets are my own).

Tailor-costumier* trying [i.e. fitting] a Fashionable Cor**

“He is dressed in a nut-brown habit coat with a black velvet collar [trimmed with] two gold buttonholes, the buttons and buttonholes of the habit-coat matching, a waistcoat [vest] of cherry-red tricot [knit fabric] with gold braid trim, black velvet breeches, and grey silk stockings. The young lady is wearing nothing but a simple petticoat and white stockings, her Cor covered in yellow-dyed batiste.”

“He is dressed in a nut-brown habit coat with a black velvet collar [trimmed with] two gold buttonholes, the buttons and buttonholes of the habit-coat matching, a waistcoat [vest] of cherry-red tricot [knit fabric] with gold braid trim, black velvet breeches, and grey silk stockings. The young lady is wearing nothing but a simple petticoat and white stockings, her Cor covered in yellow-dyed batiste.”

*A “tailor-costumier” (tailleur costumier) during this period in France was, according to Garsault, a particular trade set out by statute, which involved not only stay-making for women, but also the making of gowns, riding habits, cloaks, etc.

**The word “Cor” in French of this period was synonymous with “cors” or “corps”, meaning “body”, or in English of the time, “stays”. However, the French recognized different categories of “cors”, depending on the construction method and materials used.

**The word “Cor” in French of this period was synonymous with “cors” or “corps”, meaning “body”, or in English of the time, “stays”. However, the French recognized different categories of “cors”, depending on the construction method and materials used.

Here is another interesting point regarding the above Galerie des Modes stays illustration. The word "batiste" in French at this period (ca.1778) referred to a very fine, lightweight, quite sheer and glossy closely-woven fabric, originally (prior to the mid-18thC.) made of linen.

However this was about the time when cotton was beginning to be more widely available (from the Americas). So it's quite possible the description "son cor couvert de batiste..." could refer to either linen or cotton. In fact, by around 1790, cotton batiste was more common, and by the early 19thC., the word "batiste" had migrated into English, where it became more or less equivalent in quality to fine, semi-sheer cambric.

Apparently this 1778 French sketch even confused the authors of PoF5, as they opted in their book to describe the covering of these stays as "cotton" (see caption on sketch below). Whether a fine, semi-sheer cotton or linen covering is in the end not really relevant, since it was the fact that a lightweight, fine material was being used to cover the stays, something that at first glance seemed quite unusual.

I also wonder whether I'm seeing ripples or ruching in the front of the stays covering, i.e. a gathered effect (zoom in to see what I mean), or if that was just sloppy illustrating technique? Whatever the case, this is an intriguing bit of costume of history!

However this was about the time when cotton was beginning to be more widely available (from the Americas). So it's quite possible the description "son cor couvert de batiste..." could refer to either linen or cotton. In fact, by around 1790, cotton batiste was more common, and by the early 19thC., the word "batiste" had migrated into English, where it became more or less equivalent in quality to fine, semi-sheer cambric.

Apparently this 1778 French sketch even confused the authors of PoF5, as they opted in their book to describe the covering of these stays as "cotton" (see caption on sketch below). Whether a fine, semi-sheer cotton or linen covering is in the end not really relevant, since it was the fact that a lightweight, fine material was being used to cover the stays, something that at first glance seemed quite unusual.

I also wonder whether I'm seeing ripples or ruching in the front of the stays covering, i.e. a gathered effect (zoom in to see what I mean), or if that was just sloppy illustrating technique? Whatever the case, this is an intriguing bit of costume of history!

What this one little illustration demonstrates is how much a very careful analysis can reveal in important, maybe even essential details, and perhaps more interestingly, what questions it can raise, which in turn widen our view of historical dress.

As an experiment, try taking a look at the collection of the types and styles of garments held by any large museum intending to represent fairly recent fashion, for example, from the 1980’s to late 1990’s. Scrolling through such a collection, I think it will be clear to anyone who was an adult during those years that these extant examples usually don’t provide a balanced or very accurate representation of the clothes worn by the average person, even the average fashionable person, at the time.

Fortunately for historians of recent costume, there is a myriad of other sources to rely on, such as magazines, newspapers, television, films, personal photographs, and first-hand accounts about fashion.

As an experiment, try taking a look at the collection of the types and styles of garments held by any large museum intending to represent fairly recent fashion, for example, from the 1980’s to late 1990’s. Scrolling through such a collection, I think it will be clear to anyone who was an adult during those years that these extant examples usually don’t provide a balanced or very accurate representation of the clothes worn by the average person, even the average fashionable person, at the time.

Fortunately for historians of recent costume, there is a myriad of other sources to rely on, such as magazines, newspapers, television, films, personal photographs, and first-hand accounts about fashion.

In the end, if we can keep an open, flexible mind, ready to incorporate new material into a more fluid view of historical costume, especially prior to the 19th century, it’s possible to avoid the mental trap that can shut out further, potentially important aspects of history.

Such a trap (whether it’s called “absolutism” or “conventional wisdom”) can seal surviving examples of costume into a sort of petrified image, and keep us from properly acknowledging -- or even recognizing -- new discoveries and absorbing them into an understanding of historical costume.

So the next time you find what seems to be a bizarre aberration of 18th century fashion that "shouldn't exist", don’t dismiss it out of hand. Flag it for future reference, keep an open mind, and take the time to dig a little deeper!

]]>Such a trap (whether it’s called “absolutism” or “conventional wisdom”) can seal surviving examples of costume into a sort of petrified image, and keep us from properly acknowledging -- or even recognizing -- new discoveries and absorbing them into an understanding of historical costume.

So the next time you find what seems to be a bizarre aberration of 18th century fashion that "shouldn't exist", don’t dismiss it out of hand. Flag it for future reference, keep an open mind, and take the time to dig a little deeper!

The subject of lacing in 18th century garments came up in a costume-related online discussion recently, and I thought it was a little corner of costume history interesting enough to delve into in a bit more detail, with a few examples. In this particular discussion, lacing referred to either decorative (or sometimes functional) front lacing on garments, not the lacing closures in stays or other underclothing.

There was a variety of lacing on bodices throughout the 18th century, as you might imagine, some of it quite cleverly executed (yes, "Varietie" in the title above is the archaic spelling, just for fun). Generally, but not always, this lacing, if intended to be seen, was done in a criss-cross pattern, in contrast to the spiral lacing typical of stays. I haven't yet found any definitive source(s) for exactly why this was the case, but in many extant garments (e.g. stomachers) where bodice front lacing can still be seen, the lacing is usually criss-crossed, sometimes with a little decorative loop in the middle.

In terms of garment construction, I can think of four types of 18th century bodice front lacing -- at least as seen in the few surviving examples documented -- but there are probably more. I'm deliberately leaving out fabric bands, fancy bows (échelles), buckled bands, clasps, and the like (seen in many paintings of the era) that were also used to cross or close the front of bodices, and will be focusing rather on narrower lacing only, i.e. cord-like or fine ribbon lacing. I'm also ignoring jacket front closures, where lacing was likely more common.

Here then are the four types that spring to mind fairly spontaneously from my own recall and experience in research. This, I should point out, is not intended in any way as an exhaustive or conclusive treatment of the subject, but as a brief glimpse of this niche of historical fashion (click on "Read More" to continue):

Here then are the four types that spring to mind fairly spontaneously from my own recall and experience in research. This, I should point out, is not intended in any way as an exhaustive or conclusive treatment of the subject, but as a brief glimpse of this niche of historical fashion (click on "Read More" to continue):

1. Lacing that formed part of, and was attached to, stomachers:

This first type of bodice arrangement (apparently particularly fashionable in England in the early/mid-18th century) usually had lacing run through tiny holes or else worked eyelets along each side of the stomacher, which holes would be hidden by the front edges of the gown when worn. Often the lacing was of rich silver or gold cord, in keeping with the ornamentation of the stomacher.

There are enough such stomachers surviving to suggest this must have been a common and fashionable item during the entire period of about 1700 to the late 1770's when stomachers went out of fashion (although front bodice lacing of one style or another certainly pre-dated this period -- see further on).

The photo of the ca. 1740 sage green silk robe à la française above shows one example of a laced stomacher of the mid-18th century. Below are just a few more (forgive me if I've misplaced some of the source citations, these are images I've quickly picked up from my laptop file as illustrations). You'll find many examples of this sort of lacing on extant stomachers of the era.

This first type of bodice arrangement (apparently particularly fashionable in England in the early/mid-18th century) usually had lacing run through tiny holes or else worked eyelets along each side of the stomacher, which holes would be hidden by the front edges of the gown when worn. Often the lacing was of rich silver or gold cord, in keeping with the ornamentation of the stomacher.

There are enough such stomachers surviving to suggest this must have been a common and fashionable item during the entire period of about 1700 to the late 1770's when stomachers went out of fashion (although front bodice lacing of one style or another certainly pre-dated this period -- see further on).

The photo of the ca. 1740 sage green silk robe à la française above shows one example of a laced stomacher of the mid-18th century. Below are just a few more (forgive me if I've misplaced some of the source citations, these are images I've quickly picked up from my laptop file as illustrations). You'll find many examples of this sort of lacing on extant stomachers of the era.

Below is a closer view of the stomacher shown in the photo of the sack gown at top. I do not know whether this stomacher was original to the gown. At top right in this photo the attachment point of the gold cord lacing to the gold trim on the stomacher can just be seen.

Following is another example of this type of laced decoration, on a stomacher finished with eyelets on both sides to take the laces (dated to ca. 1740, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

Nancy Bradfield, in her infinitely useful work, Costume in Detail, describes a gown of ca. 1755-65 in yellow silk (sketches on pp 31-32), shown with a stomacher -- not original to the gown -- which she suggests is of a much earlier date than the dress (she speculates early 17th C.).

I'm including photographs of the gown, currently in the Snowshill collection (U.K.), to show how -- assuming Bradfield is correct about the possible date -- a stomacher from the 1600's with integral front lacing may have been constructed, and as a demonstration of how long this style of construction persisted. These photographs are not the best, but if you have Bradfield's book you can see all the details noted by her on page 32 (I've included an excerpt of that page below).

Notice in Nancy Bradfield's sketch of the stomacher below that the eyelet holes are done in an even pattern on the side panels, meaning that the lacing was not intended for a spiral arrangement:

2. Gowns that laced visibly at front, over a stomacher or similar bodice filler:

There seem to be few surviving examples of these types of gowns (at least not that have been well photographed), but there are enough to suggest that this arrangement may not have been a rare construction method.

As can be seen from the following, most of the useful photographs showing interior construction of these gowns have cropped up in private sales (for some reason museums tend to be less generous with photographs of historical garments -- or perhaps simply less thorough due to time and budget constraints).

In any case, in addition to the handful of photos I've found over the years, there is also clear documentation of three such bodices in modern costume research works (see below) .

There seem to be few surviving examples of these types of gowns (at least not that have been well photographed), but there are enough to suggest that this arrangement may not have been a rare construction method.

As can be seen from the following, most of the useful photographs showing interior construction of these gowns have cropped up in private sales (for some reason museums tend to be less generous with photographs of historical garments -- or perhaps simply less thorough due to time and budget constraints).

In any case, in addition to the handful of photos I've found over the years, there is also clear documentation of three such bodices in modern costume research works (see below) .

Janet Arnold's Patterns of Fashion I details just such a gown (described as a "wrapping gown") of ca. 1720-30, including this description of the bodice front: "Inside the front of the bodice are two strips of linen doubled over with eyelet holes worked in them. The gown fastens by lacing through these holes over the corset or stomacher."

This gown is in the collection of The Laing Art Gallery and Museum (U.K.). Details can be found at this link (although the photographs are not very useful):

https://collectionssearchtwmuseums.org.uk/#details=ecatalogue.267768

The gown is described as an open gown of ca. 1750, remodelled from an original mantua of about 1720, based upon both the textile design and visible stitching on the gown. Hence the wide dating range.

Here is an excerpt from Janet Arnold's book, Patterns of Fashion I (page 22), with her sketches of the exterior of the gown and the interior construction, showing the eyelet strip. These drawings are more instructive than most of the photos on the museum's site, although the "Condition Report" included at the above link has some additional photographs of the unmounted gown (see one example further on):

This gown is in the collection of The Laing Art Gallery and Museum (U.K.). Details can be found at this link (although the photographs are not very useful):

https://collectionssearchtwmuseums.org.uk/#details=ecatalogue.267768

The gown is described as an open gown of ca. 1750, remodelled from an original mantua of about 1720, based upon both the textile design and visible stitching on the gown. Hence the wide dating range.

Here is an excerpt from Janet Arnold's book, Patterns of Fashion I (page 22), with her sketches of the exterior of the gown and the interior construction, showing the eyelet strip. These drawings are more instructive than most of the photos on the museum's site, although the "Condition Report" included at the above link has some additional photographs of the unmounted gown (see one example further on):

The photograph below (from the "Condition Report" prepared by the Laing Art Gallery and Museum) does plainly show the inner bodice panels with their eyelets for lacing over a stomacher (and incidentally provides a clear image of the fabulous textile itself, not easily imagined from Janet Arnold's black and white sketch):

In Costume in Detail, Nancy Bradfield provides annotated sketches of two gowns (one at pp 17-18 and the other at pp 27-28), both dated ca. 1750, both from the Snowshill collection, with provision along the front edges of the bodice (one with metal eyes, the other with sewn eyelets) through which a cord could be laced over a (missing) stomacher. (As an aside, I know I've seen someone post photographs of at least one of these gowns -- presumably from a visit to the Snowshill collection -- but I can't seem to locate them now that I want them!).

So, failing photos of the two gowns themselves, I've included excerpts of Bradfield's sketches below.

Bradfield speculates that the stomacher of the second gown may have included bows in the French style (in addition to the lacing), although this seems unusual. She includes a sketch (also shown below in the second panel) of how the gown might have appeared with its missing stomacher, with the lacing run through the lace at the top of the stomacher before being criss-crossed down the front. The robings along each side of the bodice would then be pulled in and pinned in place on each side, hiding the eyelet strips.

So, failing photos of the two gowns themselves, I've included excerpts of Bradfield's sketches below.

Bradfield speculates that the stomacher of the second gown may have included bows in the French style (in addition to the lacing), although this seems unusual. She includes a sketch (also shown below in the second panel) of how the gown might have appeared with its missing stomacher, with the lacing run through the lace at the top of the stomacher before being criss-crossed down the front. The robings along each side of the bodice would then be pulled in and pinned in place on each side, hiding the eyelet strips.

The second, similarly styled bodice documented by Bradfield:

In the few gowns I can recall of this type, the stomacher has usually gone missing long ago. We can never know for certain what the stomacher for such a gown might have looked like, although the fairly restrained decoration of gowns of this era (1720-50) might suggest a simple embroidered or smooth stomacher would be appropriate. I have a couple of examples of extant gowns with front bodice lacing which apparently retained their original stomacher or front section -- see the photos of these further on.

Visible, decorative front lacing on jackets of the era is well documented (there are a number of paintings and extant jackets in museum collections to testify to their construction), but there are few paintings of women wearing gowns with visible front lacing. It is pure speculation of course, but the paucity of portraiture leads me to wonder whether this style was considered somewhat déshabillé or négligé, i.e. perhaps something to be worn in leisure hours or by the lower classes. In other words, not grand enough for a fine lady's permanent memorial in oils.