|

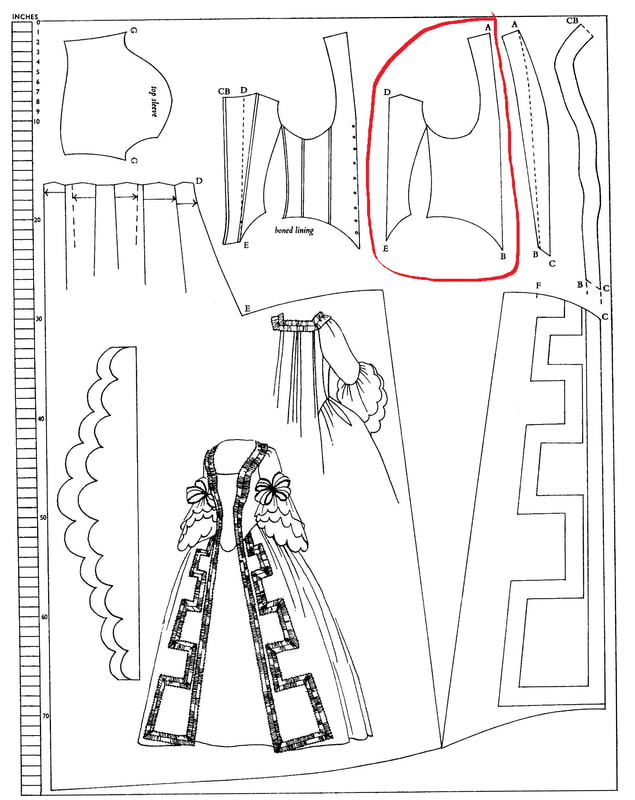

One question that comes up frequently in online historical costuming discussions is that of how much fabric would be needed to cut a particular type of gown, or else how best to make use of available yardage. This was certainly a serious question in the 18th century, when the high cost of materials (particularly silk) meant that an effort was made to use every possible scrap of fabric to best advantage in constructing a gown. This is revealed in the many ways in which garments -- particularly silk ones -- were cleverly pieced. In this article I'd like to focus on the problem of estimating yardage for a typical robe à la française (known in English as a "sacque" or "sack" gown. (Click on "Read More", lower right, to continue) For those who may not be familiar with the terminology, a robe à la française, or "sacque" gown was a fashion that developed around the late 1730's from an earlier, rather loose and informal style of gown introduced (or so it's said) into the court of King Louis XV by one of his mistresses to conceal a pregnancy. This was a robe constructed more or less along the lines of a very loose kimono with flowing back pleats, called the "robe volante" ("flying gown") or sometimes "robe battante" ("beating gown"). Both of these names arose from the fact that courtiers found these gowns, with their enormously wide silhouettes and hemlines, to take up far more space than the earlier, more vertical mantuas. This style of gown, originally a very informal piece of déshabillé (undress), faded from fashion fairly quickly, being transformed by the late 1730's through the introduction of a little more waistline definition and a little less volume around the torso, into that iconic gown of the 18th century, the robe à la française (French-style gown), or sacque/sack gown (the term "sacque" was in use in English in the 18th century). The robe à la française was a style that, with a few changes in construction and details (especially the width at the hips) was to remain fashionable from the 1740's through to the very early 1780's. And no wonder! With its elegant flowing back pleats, fitted bodice, defined waistline and graceful lines, the sacque gown enhanced practically any woman's appearance. At first this type of gown was considered -- especially in the French court -- as rather informal, but later in the century became the epitome of 18th century formal dress. By the beginning of the last quarter of the century, the robe à la française was made in all types of fabrics (including silk and various blends of textiles, as well as cotton prints that were becoming so fashionable by the late 1770's), but silk was the textile that made the most of this wonderful style of dress. I was recently able to purchase some beautiful silk taffeta on sale that had a brocaded floral motif on a lengthwise stripe of soft sage green and warm tan -- perfect for a robe à la française. I had ordered 13 metres, thinking that would be just enough for the gown, a matching petticoat and stomacher, and all the furbelows and trimmings I might want to add. Unfortunately, after ordering, the company called to advise that they had only 9.5m left (about 10-1/4 yards) -- and did I still want it? I took a deep breath, quickly calculated my options (fairly certain of my ability to work out a solution), then said yes! I'm sure I'm not the only one who has ever been in this position. This experience gave me the idea to offer some tips and thoughts on yardage requirements for a sacque. Silk may not be as costly for the average person as it was in the 18th century, but it's still an expensive investment for an historical gown. So anything that can be done to maximize the use of available yardage is a good thing. Do I Really Need a Pattern? The answer is probably not, provided you're willing to do a little research (which in itself can be interesting, even fun). A pre-designed, printed sewing pattern for a sacque gown would seem to make calculating yardage easier, but the problem with such patterns is that (a) good ones are rare; and (b) they are often standardized for an average style and average figure, and may not take additional personal design choices into account. Most accomplished makers of 18th century reproduction clothing that I know of don't use pre-printed commercial patterns to cut gowns, particularly not a robe à la française. This is because they understand the basic contours and shapes of the style, knowing that such a gown would have been constructed to fit the specific wearer's body. They also know that working from a general knowledge of the cut of such a gown and draping and fitting the pieces on the body is actually more efficient and precise than using a pre-printed pattern. Beginners contemplating making a beautiful sacque gown may be in awe of such ability, especially when confronted with the daunting task of cutting into metres of expensive silk, but the concept is actually fairly straightforward. Once learned, it can be applied to virtually any gown of this type. My aim in this article is to offer general guidelines for those who are unfamiliar with the process of 18th century garment-making in general, and to provide some specific pointers on estimating yardage, not primarily on construction methods. In approaching making a robe à la française, it's important first of all to put aside all ideas of modern sewing patterns -- start on a mental blank slate, so to speak! On that blank slate, to begin with, should be the concept that an 18th century sacque (in fact almost any 18thC. gown) would be built up on a closely-fitted "lining", usually made of linen. It's generally referred to it as a "lining", but this is not a lining in the modern sense. I prefer to think of it as a fitted "underbodice". Once the lining is properly fitted on the person who will wear the gown, all the rest is like layering on a collage. Accordingly, my first advice would be to create your own "template" for your gown's lining (underbodice). The pieces involved are quite simple, forming the understructure or scaffold on which the rest of the gown will be mounted. From there, calculating yardage for your sacque gown should be fairly simple, based on a few style choices. The lining of an 18th century gown was almost always cut from linen, so you can eliminate that part of the project from your fashion fabric yardage calculations. Normally about 1.0 to 1.5m (about 1 to 1-1/2 yards) of modern wide linen will be needed for these pieces (which will include the sleeve linings). Note that the bodice lining shown in the photos below is sleeveless because the sleeve linings will be made up with the sleeves themselves before the sleeves are sewn onto the bodice lining. Remember: these pieces must fit your body, so there is no "perfect" pattern. Start by drawing out the general shapes needed, including generous allowances to permit re-cutting and fitting, keeping in mind the ultimate style of your sacque's bodice. Then make your personal, custom-fitted template. A few trials and errors might be needed, but once you have your fitted lining completed, the rest of the gown is a matter of draping and fitting to the lining. There are currently many resources available, both in print and online, that provide the basic outlines of pieces generally used for gown linings of this type. Two that I would recommend as particularly helpful for anyone just starting with 18thC. gowns are: "Costume in Detail" by Nancy Bradfield, and Patterns of Fashion I (by Janet Arnold). The former book has no cutting diagrams per se, but a wealth of detailed information on cut and construction. The latter volume has a limited number of garments from the era, but clear, reduced-scale cutting diagrams that provide a good basis for drawing your own pieces. Initial Considerations in Calculating Yardage for a Sacque There are a few preliminaries you'll need to consider before you can calculate how much fabric you'll need for your sacque: (1) How wide is your fabric? 18th century silks in particular were made in narrow widths -- between about 50 to 70cm wide (20" to 27" wide). Almost no fabric is this narrow today, but fortunately many silks and cottons are easily twice this width. Some vintage silks are around 90cm (36") wide, a problem I'll discuss further on. (2) What style of sacque are you making? Although the basic style of the robe à la française remained fashionable from about 1740 to the late 1770's, there were variations. Earlier styles tended to have wider, fuller back pleats, wide hips, and vertically pleated front edges, as well as wide, deep cuffs. They mostly had very little in the way of applied trim or embellishment. Later types had somewhat narrower back pleats and sleeves had single or multiple flounces, or later ruched applied bands. More applied surface decoration, usually made from the same fabric as the gown, became the norm in the mid-1750's to early 1770's. Formal sacques had extremely wide panniers, petticoats and gown skirts, whereas an "everyday" sacque of the 1760's could be made with almost a natural silhouette, worn over no support (hoop petticoat) at all. Most fine sacques had trains; less formal styles were "round" length (floor length) all around. A few examples of these variations are shown below.

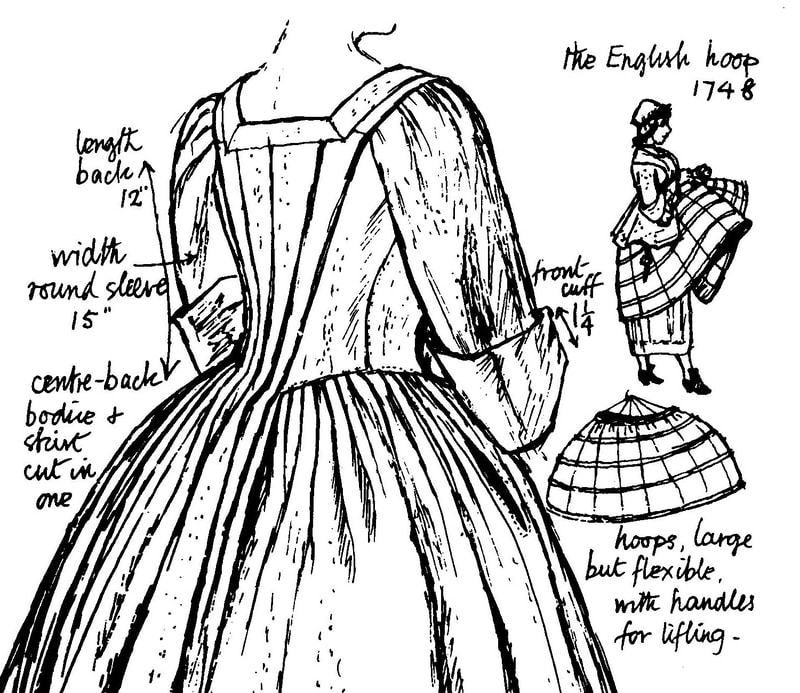

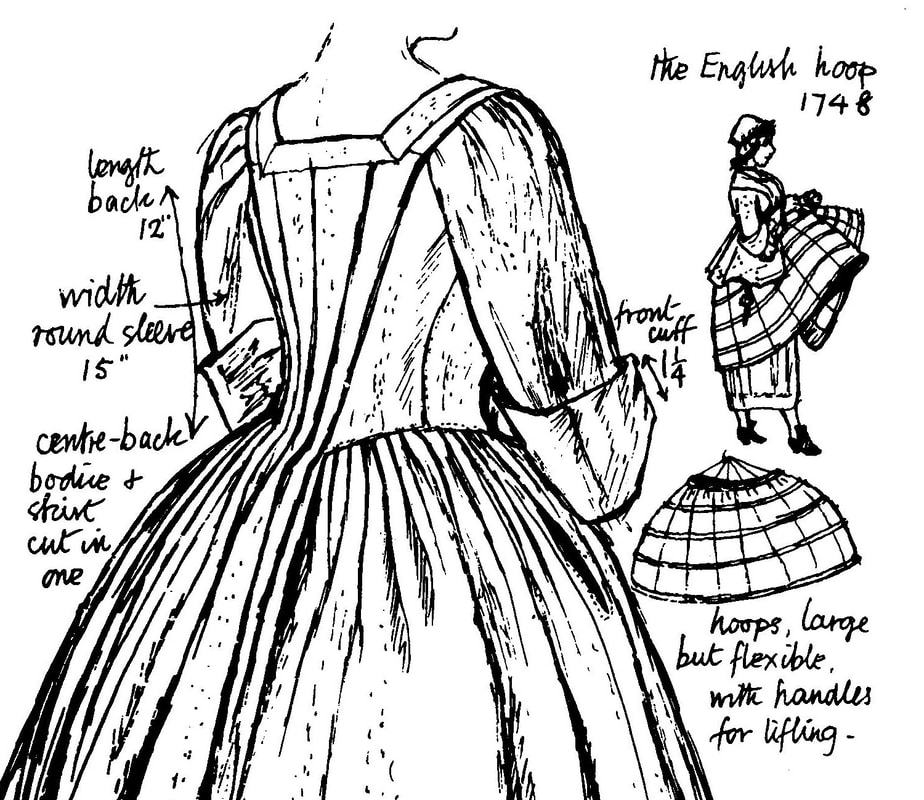

(3) What sort of support do you plan to wear underneath? In the 1740's, hoop petticoats almost as wide as those of the 1860's crinolines a hundred years later, were worn under dressy sacques. In the mid-18th century more moderate side hoops were fashionable, but more formal gowns had excessively wide panniers ('grands paniers'). Some examples are shown below. (4) What is your size, shape, and height? These factors on their own won't be too significant, but should be taken into account with other style considerations. (5) What sort of embellishment are you planning? As noted above, earlier sacque gowns were quite plain, relying on the beauty of the silk alone, whereas after the early 1750's and especially toward the 1770's, extensive surface embellishment became common, such as ruched or pleated furbelows or meanders, or later puffed serpentine designs. These were generally made from the same fabric as the gown, and depending upon extent, could take quite a lot of yardage. Some examples of these types of decoration follow:

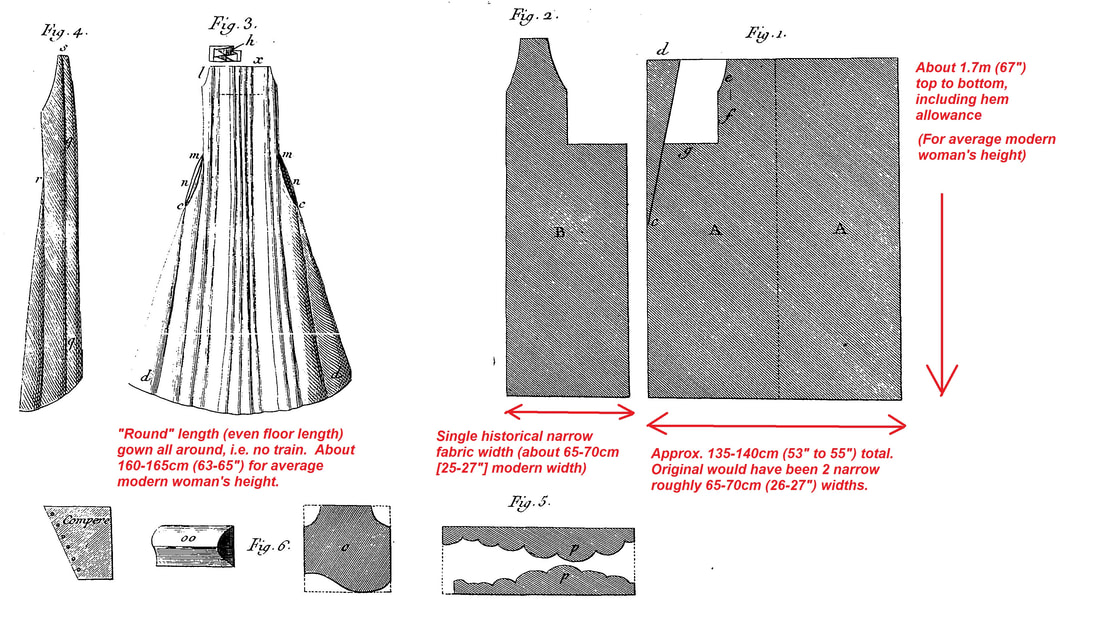

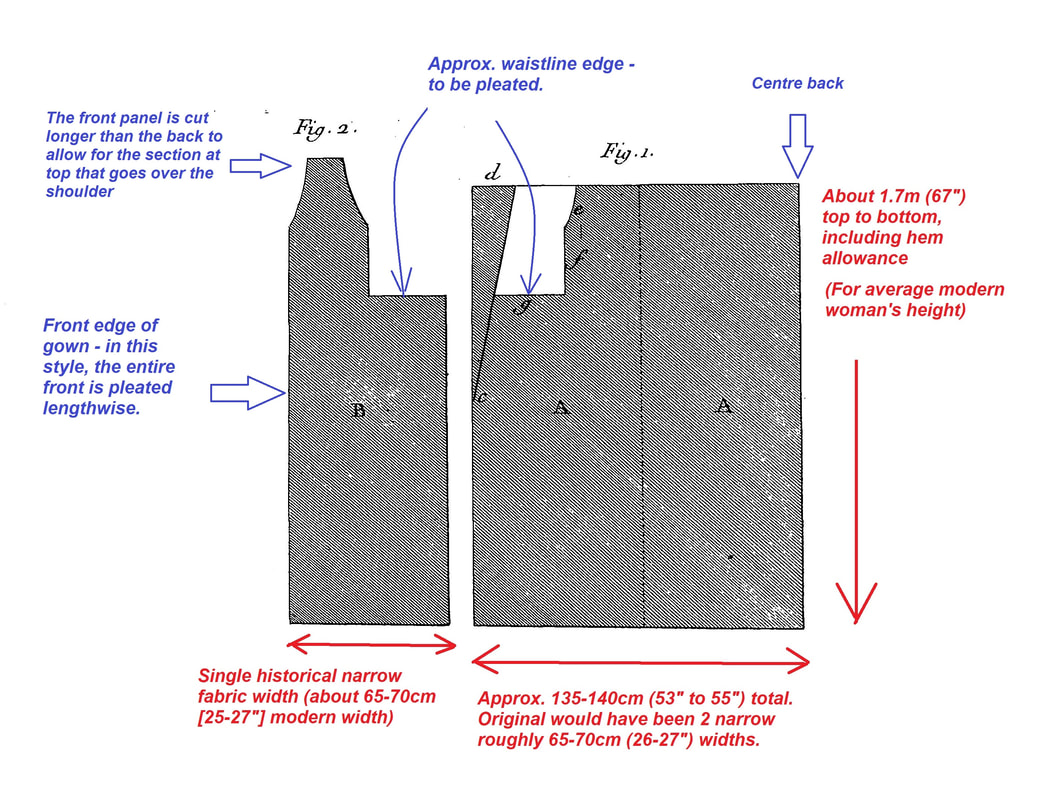

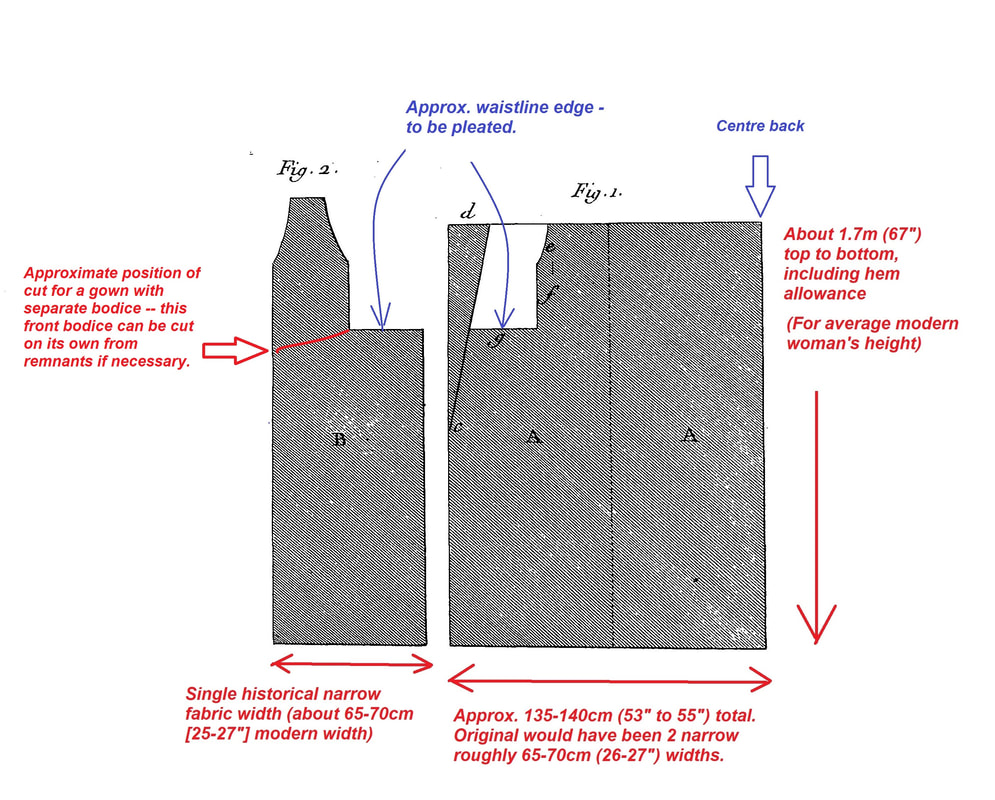

(6) Are you planning a matching petticoat? If surviving examples of 18th century sacque gowns are a guide (and there are many of them), most, especially those made of silk, had a matching petticoat, usually with some form of trimming made from the same material. There are ways to "cheat" on a full petticoat, which I'll discuss further on. Determining Yardage for a Basic Sacque We thankfully have the rare and helpful contemporary record made by François Garsault, around the mid-1760's, outlining in relatively good detail the requirements for, and construction of a basic sacque of the era. This appeared in his L'Art du Tailleur (The Art of the Tailor). Of course, the 18thC. measurement system in France (and elsewhere) for dealing with fabric differed widely from today. As a result, Garsault's details of lengths, widths, and fabric requirements are difficult to grasp in relation to modern measurements. The "average" Frenchwoman in his time would also have been shorter and smaller in build than today's standard women's medium sizes. Accordingly, I've taken the liberty of marking Garsault's cutting diagrams with modern measurements, to more easily calculate total yardage needs. Below I've made some additional annotations (in blue) concerning construction and how the pieces fit together. Note that in Garsault's diagram above, the triangular section marked c through d was intended to be turned upside-down and sewn into the side seam below the pocket openings, as indicated in the sketch showing the back of the gown as constructed. This of course would be optional, as a means of providing extra shaping to the skirts where the panels are narrow, without using additional yardage. (This V-shaped piecing is not seen in the majority of scaled patterns of extant gowns, nor in most surviving gowns themselves, especially those that have an extra width between front and back panels). The blank space created by the shaping cut at e, f, g could be used for smaller pieces, such as the shoulder or upper back finishing strips, or pieced to furbelows. There are four important factors to note in these drawings:

It's clear from extant gowns and documented studies of construction that sacque dresses existed that were cut quite differently from Garsault's model. Many were cut with the bodice front as a separate piece (there are examples of this in Nancy Bradfield's excellent book, Costume in Detail, and in Norah Waugh's The Cut of Women's Clothes). Some later gowns were cut without an integral allowance for front pleating (robings), these pieces being cut as separate 'strips' only for the bodice. In other cases, both the bodice front and side front/side back sections were cut separately from the rest of the gown. These factors have implications in terms of yardage requirements that I'll discuss a bit later. Here, I've superimposed on Garsault's diagram a line to show approximately how the separate bodice section would be cut: Still, we can certainly use Garsault's diagrams as a useful visual starting point for estimating yardage needed for practically any robe à la française. Keep in mind that Garsault was showing only one-half of the garment in his illustration. First Things First... Let's start with some assumptions for our "typical" modern sacque reproduction:

Using Garsault's diagram, it can be seen that 4 widths of narrow 18thC. silk were required for the back and the side-back of the gown as far as the pocket opening. This includes enough for the lovely back pleats. For our 5'6" model, each of these back panels should be 1.7m (about 67") long, to allow for a hem of about 5.0cm (2"). For the front panels, an additional approximately 10cm (4") should be added (for the extra at top), for a total length of about 1.8m (71"). Therefore, the total yardage needed for the main sections of the gown (i.e., not including a matching petticoat or any surface trim) will be approximately 5.2 metres (about 5-3/4 yards):

For the sleeves, compère (or stomacher), and sleeve flounces (or cuffs), allow another 1.2m (about 1-1/2 yards). This brings the total to about 6.4 metres (approximately 7-1/4 yards). Using the Widest Modern Fabric in an Unusual Way: There is one point to add to the above yardage calculation: if you're lucky enough to have fabric that is close to 152cm (60") wide, and the gown is for an average figure of moderate height, it is just possible, with careful arrangement and judicious pleating, to make the basic gown from just two panels of about 2.0 metres each, by creating a single centre back seam between the two and using the selvedges of each panel as the forward edges of the gown. I've done this myself in a pinch when trying to squeeze a robe à la française out of less than 5 metres of silk. You won't have much left at all for embellishment, you won't have luxuriously generous back pleats and train, and you won't be able to make a matching petticoat, but you will have a basic gown constructed out of only 4 metres of 152cm (60") wide fabric. Some people may read this and say -- but that's not at all historically accurate! Well, my approach to 18thC. gown design and draping is to apply 18thc. principles, rather than slavishly copying or mimicking practices that make little sense for modern textiles. 18th century makers were working to the very best advantage they could in what they had available, which was narrow fabric often less than 60cm (24") wide, minimizing waste at all costs. Since most silks are now wide (137cm or more), it makes perfect sense to make the most of this width in a similarly practical way. With wide silk, I find that one 2m long panel can be used for each half of the body for a sacque gown, with virtually no waste of fabric. The remnants that are cut off are perfect to use for trimming, etc. You'll see my process in the photos below. This does mean creating a (rather terrifying) cut into the middle side of the material to create the pocket access opening and drape around the torso, but once done, the rest is easy, and any cut-away bits can be useful for trimming or even small bodice sections like shoulder or upper back finished strips, or even sleeve flounces. If you're fortunate enough to have 6 metres (about 6-1/2 yards) of 152cm (60") wide fabric, you can probably also cut a matching petticoat. For trimming ideas that don't require more fabric, see "Cutting Corners and Saving Graces" further on in this article. To Seam or Not to Seam? At this point (assuming you're using the standard approach to cutting your panels, and your fabric is less than about 150cm [58"] wide), you can decide whether or not to either cut the 2 back panels in half lengthwise to create more historical fabric widths (which means making 3 long vertical seams, one at centre back and one on each side, to join these panels), or to leave the full modern width and simply make one seam down centre back to join the 2 back panels. A third possibility is to create "faux" narrow vertical seams to mimic where the seams would be in 18thC. gowns made of narrow fabric. Whichever method you choose will make no difference to the yardage requirements. The back sections will be sufficient to create substantial pleats in the back of the bodice, with enough width left to go as far as the side of the torso, and the wide modern yardage will still need to be cut in half lengthwise to be used for the front panels. The back panel arrangement places selvedges conveniently along the pocket edges. Naturally, you will need to adjust the depth of pleats at centre back to accommodate your own size when draping and fitting. The photo below shows how the back panels, once pleated, fit across the back of the torso, with room to spare for pleating above the pockets. The excess fabric along the outside edge of the back will be cut (like Garsault's diagram) in a gentle curve around the armscye and down the side, and the remnants of fabric used for trimming, finishing, etc. The Petticoat Petticoat yardage is quite easy to calculate if you have modern wide yardage. For a typical petticoat, made entirely of the same fabric as the gown, about 2.3 metres (about 2-1/2 yards) of fabric at least 115cm (45") wide will suffice, assuming a 5'6" personal height without shoes. This includes reasonably generous hem and finishing allowances. Of course, at the narrower end of fabric widths (115cm/45"), you'll have less fullness in your petticoat, at the wider end (150cm/58" or more), you'll have a much fuller petticoat. I like to use one panel of the full width of fabric that is anywhere from 122 to 153cm wide (about 48" to 60" wide) for each of the back and front. This places all four selvedges conveniently at the sides, where the pocket openings will be. The only real consideration will be length (i.e. based on your personal height and on the width of your panniers, hoop skirt, etc.). If your fabric is narrower than about 120cm (47"), you'll need to decide whether you can live with a less full petticoat, or prefer to cut additional half-width panels to create more fullness (of course this will require more fabric). To see a detailed discussion on planning, cutting and constructing a petticoat from narrow (90cm/36") fabric, see my blog on the 1764 Countess Howe Gown at the link below. Although this was an English gown, the petticoat was the standard type used with open gowns. Summing Up Thus far, we have the following yardage for our round length gown:

To be safe, I would recommend rounding this up to an even 9.0m (about 9-3/4 yds), to allow for slight variations and/or cutting errors. Now for the Add-on Options! Like buying a car, you'll need to decide what (if anything) you want or can afford beyond the plain vanilla model. However, unlike buying a car, there are a few corners you can cut to save on fabric, especially if you have a limited length of yardage and can't get any more of it. First, I'll outline the possible add-on options: For the following options, add the indicated extra to the basic yardage of 9.0 metres (9-3/4 yards). Remember that the add-ons mentioned here will need to be cumulative for all the extras you're planning to include:

Keep in mind that you may want some of the trim (e.g. on the petticoat) to be wider, which will reduce the amount of available trim for the gown itself. An extensively trimmed gown and petticoat may require up to 3.0 metres (3-1/2 yards) or more of additional fabric. My best advice: if you're planning a heavily self-trimmed gown and you can afford it, err on the side of extra fabric.

Given our initial basic yardage of about 9.0 metres (9-3/4 yards), if all of the above "options" are included, it's possible that a total of roughly 11.5 metres ( 12-1/2 yards) would be required to make a gown with most of the fancy additions seen on a dressy (but not highly formal) mid-century robe à la française. To be safe, 12 to 13 metres (about 13 to 14 yards) of 130-153cm wide (51" to 60" wide) fabric will allow for a variety of creative leeway in design, style, or size choices. This is the ideal for a typical sacque if you're able to afford it, and assuming that enough of your desired fabric is available from the retailer. As noted earlier, add at least another 2.0m (2-1/4 yards) for a gown worn over very large panniers. Which explains why I ordered 13 metres of my lovely silk, only to have to settle for the 9.5 metres they did have! So now comes the noodling... Cutting Corners & Saving Graces So, you know you're likely a bit short on yardage, but still want to create a beautiful sacque gown -- somehow! Here are some suggestions that may help: (1) When in the 18th century, do what the Georgians makers did: There were clever methods used by 18thC. gown makers to economize on fabric, especially on costly silk textiles, that you can use today. These include:

Below are a few examples of the clever 18thC. ruses and options that I've mentioned:

(2) Other Ruses and Corner-Cutting

Final Thoughts

Making a robe à la française (or sacque) is a big investment in materials and time, so it's worth carefully considering in advance how your design choices will affect yardage. I hope these guidelines will be helpful for your next project! So you might wonder: what am I planning to do with my less-than-ideal 9.5 metres of silk? Well, thankfully it's wide (137cm [54"]), which means I will certainly have enough for the gown, but I'm going to need to be careful with the rest. The gown will be a slightly trained sacque in the French style of ca.1760, worn over a moderate set of panniers (one inspiration painting is shown below), with matching stomacher and petticoat, and flounced sleeves. The bodice will be cut separately, using the silk saved by making a faux upper back to the petticoat. If I get all that out of about 8.5m of my silk, I may have a little left to use as ruched trim on the bodice, or perhaps to mix with lace as trim to make it go farther. One way or the other, this fabric deserves to be a robe à la française, and maybe I'll even get to wear it somewhere in 2022. Check back again to see my progress -- and happy sewing!

8 Comments

5/10/2021 03:02:09 pm

Very well-researched and helpful! I appreciate that you've included so much helpful information on the changing styles and varying options in addition to the mere yardage calculations.

Reply

5/10/2021 06:48:51 pm

Thanks so much for your kind words, I'm very glad you found this article useful!

Reply

Molly

6/10/2021 02:02:56 am

Wonderful article! I was pondering the same things because I got my hands on 7.5 yards of an 18th C reproduction brocade that is virtually impossible to find, but even at 4'11" cannot get a full sacque out of that. My plan is to go for one of the relatively less common sacque gowns that have a closed front instead of separate petticoat from ~1740 (luckily there is one in the new edition of Patterns of Fashion!). I think between that, my height, and the lack of self-trim in that era I should be able to just squeak it out.

Reply

21/7/2022 02:32:04 am

Thanks for sharing this useful information! Hope that you will continue with the kind of stuff you are doing.

Reply

Leslie Thaggard

18/6/2023 11:28:07 am

This is a well researched and presented article. Thank you so very much for this information. I especially like your photos of museum art and existing gowns. Most helpful. This is to be my summer project. Wish me luck. Leslie

Reply

Helen Bayley

28/12/2023 09:18:28 am

Thank you for such a helpful article.

Reply

Rosanna Dill

17/3/2024 10:46:20 pm

This is very helpful! Thanks! I’m smaller than the modell you based this on and at 5’21/2” barefoot, I think I will be able to go with less. Great analysis!

Reply

5/8/2024 03:13:09 pm

Thank you for such a wonderful article! I did have a question though. I am wanting to make a formal/court sacque gown for my wedding gown. The official date has not been set yet. I have not bought the fabric yet and am likely going to want all the options however I noticed you only made mention of the formal sacque gown but didn't actually get very deep into the details... If i'm going to be able to make the wedding gown of my dreams, I need details on that please? At this point i'm thinking 20 yards or more is what i'm going to have to buy, but I am uncertain.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPatricia Preston ('The Fashion Archaeologist'), Linguist, historian, translator, pattern-maker, former museum professional, and lover of all things costume history. Categories

All

Timeline

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed