|

This is the first in a planned series of articles intended to help familiarize sewing enthusiasts with the origin, botanical features, history, and production of fabrics available to them, especially considering textiles which may be thought of as having similar characteristics. This Part 1 will look at the two linen "twins": ramie and true flax linen, which are really more fraternal than identical twins. Whether your focus is on historical reproductions or modern sewing, I hope you'll find something useful in these articles to guide your choice of fabrics. What's the difference between true linen (flax) and ramie?Linen textiles come in a diverse and beautiful array of weights, weaves, textures, and colours, for use in everything from fine blouses to upholstery. Yet many people are unaware that a linen-like fabric called ramie exists, or if they do know of ramie, may believe that there is little to distinguish it from true linen made from flax. Actually, there is quite a difference between these two fibres. Although both are plant-based fibres, the plants from which they come are completely unrelated botanically (see more about this further on). Flax is grown as an annual in northern climates (dies down at the end of the season), whereas ramie is a perennial, grown mostly in humid, tropical or semi-tropical regions. The process required to turn them into cloth is different, and the resulting textiles, although somewhat similar in nature, are in fact quite distinct, with unique characteristics that set them apart. Linen (flax) and ramie are both ancient fibres. Flax linen is known to have been made by the ancient Egyptians, and has amazingly survived (most notably as mummy wrappings) for thousands of years, given the right climate conditions. It has been in cultivation and use for textiles ever since. Ramie is believed to be even older, going back possibly 5,000 years or more in the Orient. Today, Canada produces the majority of the flax sold on the global market (over 750,000 tonnes). The other major producers of flax, in order of tonnage are: Kazakhstan, China, Russia, United States, and India. France, Belgium, Ireland, Italy, Ukraine and Argentina produce smaller quantities, the flax from the first four of these countries being particularly valued for high-end textile production. Recently the Baltic area and Poland have seen an enormous growth in the linen thread and textile industry, particularly for home décor uses, such as bed linens, draperies and other household linens. Garments made of linen are beautiful, eminently comfortable (especially in hot weather), and long-lasting, giving linen a prized place in mankind’s textile choices for centuries. Ramie’s use as a textile may go back even further than that of flax linen, as ramie is an oriental native, having originated in China or Malaysia (or possibly both, as slightly different varieties are grown in these regions). It is also believed to have been known in ancient Egypt. The common name used today, ramie, comes from the Malaysian word rami. Since ramie is grown mainly as a moist-tropical plant and is perennial (no re-seeding required each season), usually more than one crop per season can be taken off the same acreage, making it an economical textile plant. Today the primary ramie-growing areas of the world are China, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea and the Philippines. Both plants (flax and ramie) have been used by mankind for millennia for a variety of purposes aside from textile-making, and both are sources for the manufacturer of valuable utilitarian and industrial products, as well as providing edibles. Here is a look at the plants themselves and the products (including textiles) that are made from them, followed by a description of the qualities of each of the fabrics made from these plants that may be helpful in identifying and distinguishing one from the other. Incidentally, ramie is quite distinct from hemp or other natural plant fibres such as jute and bamboo (a subject which I’ll deal with at a later date). As a rule, the general term "linen" can apply to flax, ramie or other bast fibre textiles (more about this further on). Linen (Linum usitatissimum)Linen is most often associated with true flax, a member of the plant family classified under Linaceae, consisting of about 160 species, mostly native to the temperate (northern) regions of the world. The flax plant’s origin is murky, but it’s likely native to the eastern Mediterranean or near east. Flax is still grown primarily in the north temperate areas of the earth as an annual crop (that is, one that must be sown each spring), and is the plant from which most European linen has been traditionally made. Flax is often referred to interchangeably as "linen", although as I'll discuss later on, the word "linen" has been used to apply to other textiles. There is a good reason this very pretty, deceptively delicate-looking plant was given the designation “usitatissisum” by botanical cataloguers: the Latin term means “of the greatest use”, or “most useful”, that is, to mankind. And so it is! Flax is one of the most valuable plants humans have had available for millennia (especially in northern regions) not only for more recent, or larger-scale commercial production, but also as a means of local and home-based textile production. There are many people today who still like to grow, process, spin and weave their own flax fibre into fabric in the traditional, ancient way as a hobby or local eco-business. On an industrial scale, linen is big business in northern countries, whether for seed, oil, or textiles, and harvesting and processing is largely now done with modern machinery: Aside from the lovely garment textiles made from this plant, flax has been used for an incredible diversity of purposes, including:

The beautiful textile made from a plantNext to silk, linen is arguably the most beautiful natural textile made. Despite its tendency to wrinkle (which is seen by many as a positive sign of its natural quality), linen fabric is smooth, cool, and wonderfully comforting against the skin. It has both a slight springiness and yet good drape. Linen is unmatched as a “breathable” material, having the rare dual properties of being able to absorb a great deal of moisture yet also dry very quickly, the ideal cooling fabric for hot weather. It is mold and mildew resistant and unbothered by moths. Linen takes dyes less readily than some other fabrics (such as silk or cotton), but has a subtly lustrous surface and can look beautifully elegant even as an undyed textile. Due to the slightly uneven nature of the natural linen fibre, textiles made from true flax linen almost always show slubs (that is, occasional thicker portions in the weave) to one extent or another. Linen is stronger when wet than dry, will stand up to repeated hard washings and actually become softer as a result, a characteristic which made linen the ideal, long-lasting, healthy undergarment (shift) to wear next to the skin in the 18th century. Somehow we’ve forgotten that wisdom! It was frequently used to make middle and lower class stays in the 18th century as a less expensive alternative to silk (see the example pictured below). Linen can withstand high temperatures (e.g. by ironing) and hard compression, such as through mangles (machines used over a century ago to press linens flat, creating an smooth, lustrous surface), or a combination of both (as in calendering to produce a glassy, ciré-like surface). Flax linen is manufactured in a wide variety of weights and textures, from the finest, sheerest handkerchief linen to the heaviest upholstery fabric. Linen’s one drawback, aside from its tendency to wrinkle easily, is that it is not as abrasion and stress-resistant as some textiles, particularly at points of wear, such as tailored edges or joining seams subject to strain. Like metal, but unlike wool which is flexible even when dry, linen can be brittle at such points and eventually break. However, linen’s admirable qualities more than outweigh these negatives. A multi-step process is required to transform flax from plant into a magical linen textile. The linen-making method, while not as simple as cotton or wool, has always been straightforward enough to be done in a home or local setting. For centuries in the Low Countries most notably, but also in other flax-growing regions throughout the temperate regions of the earth, fields of flax were harvested by hand, the flax plants being pulled out by the roots rather than being cut like wheat, in order to preserve the longest possible fibres. The traditional linen-making steps, which go back hundreds, if not thousands of years, were carried out by hand as well. These were, in general terms:

There are various means by which the outer sheath of the flax stalk can be retted (rotted away), including in a still pond, vats or tanks, laid out on grass to expose the stalks to the dew, using chemicals to break down the stalks, or – the traditional preferred way – in a stream or river. It is generally acknowledged that the quality of flax linen fibre is directly related to the retting method used, dew or vat-retting producing a greyish-beige coloured, coarser fibre, and stream-retting a finer blond coloured fibre (hence the expression “flaxen-haired girl”). The photos below demonstrate the difference between the finest, lightest fibre and that of coarser, lesser quality flax fibre, both after final hackling. Completing the process of scutching and hackling (or heckling) to get to the resulting flax fibres as shown above does take muscle-power, but linen-making is often shown in old paintings and illustrations as being a communal or family activity. The finest and most expensive linen was white, made in the traditional manner as the product of "grassing", i.e. the long lengths of woven linen laid out on grass to be bleached naturally by the sun. This process could take days or weeks, depending upon the weather and the amount of sunshine. Below are: (1) a painting by Teniers from about 1640 showing a community bleaching-ground in the Netherlands, and (2) an early 20th century photo-postcard from Ireland, showing linen laid out on grass for bleaching: Despite the demands of these processing activities, linen-making has been able to be scaled up to commercial production through mechanization more easily and economically than ramie. This is because, unlike ramie fibre, there are no difficult gummy substances to be removed from flax stalks nor fibres that require high heat or chemical extraction. Bleaching flax linen to a fine white still remains challenging however, even with modern chemicals and processes, as it is a delicate balance between obtaining a pure white or damaging the natural beauty of the textile. Since finished linen fabric often contains a high percentage of impurities (about 20% in comparison to cotton's 5% or less), including plant material and waxes which help to give linen its subtle gloss and interesting slubbed texture, it is harder to bleach than cotton, and the process takes longer. Accordingly, even today pure, absolutely white linen is usually more expensive than "natural white". These days, in larger linen-producing nations like Belgium, the traditional processing steps are done by a variety of specialized machinery. Yet the great advantage to modern linen production is that the cleaning and dressing can be done entirely mechanically, without the use of chemicals (at least until the dye stage). In addition, none of the debris removed is discarded -- every part of it is useful. Each step of the process of producing fine textile linen from flax results in a product that can be used in some way by a number of industries, whether for paper, composite board, animal feed, rope/twine, or rougher linen fabric. Where textiles are concerned, linen has a small ecological footprint and a sustainable economic profile. Linen reigned supreme in Europe for centuries as the textile of both aristocrats (in its finer, whiter forms, especially in lace) and of the middling and working classes (in ordinary quality and homespun form). In North America, colonists in northern areas developed local linen growing, processing and weaving, and were often required by authorities to produce a certain amount of home-made linen textile. The dominance of linen was finally crushed by the enormous quantities of cotton that began to flood the British and European markets by the end of the 18th century. The lucrative cotton trade, largely made possible by the enslavement of Africans in the United States of America, produced a textile with many of the natural properties of linen, but that was cheaper, quicker, and easier to manufacture than linen. Nonetheless, throughout the 20th century, flax and linen textile production still accounted for a meaningful segment of the economy of many northern European countries, as well as parts of Canada, the U.S., the U.K., Scotland, and Ireland. Although prior to WWI much of the field and preparatory work was still done by hand and horse-power, the linen industry operated on an enormous scale, manufacturing everything from fine damask linens to ropes and sails for ships. From the late 1890's to the mid- 1910's, linen enjoyed a resurgence in popularity for fashionable clothing, especially for warm weather walking suits, dresses, and blouses. In Europe however, the devastation of the two World Wars (and particularly WWI) wrought havoc on linen production, since many of the areas used for growing flax saw long, devastating battles that razed and tore up the landscape. Flax growers and weavers were forced to abandon their occupations and flee. In particular, the flax fields of Belgium and the Netherlands never recovered their former extent. Perhaps even more tragically, most of the varietal diversity of flax genetics, perfected over hundreds of years of selective plant breeding in Europe, was lost. The highest quality flax linen produced today can't compare with the incredibly fine, beautiful linen of the 19th and early 20th century prior to WWI, made into delicate items such as silky, gossamer handkerchiefs and sheer blouses. This loss of flax varieties is the main reason identical textiles cannot be manufactured today. The hope is that perhaps enough genetic diversity remains amongst all the common flax grown today that, in time, a few flax plants will be discovered that have these exceptional qualities in their fibre, and which can be propagated by seed once again. Like the other natural fibre textiles, linen has a history that parallels and follows that of humankind itself. Linen textiles todayToday linen is made into a mind-boggling array of textiles in various weights and weave patterns. About the only type that is not seen in linen is satin. This is because linen fibres are too brittle to be effectively “floated” for any great distance over a base warp (as silk can be). It may also be that since the surface of linen can be rendered satin-smooth, glossy and hard through mechanical means that weaving linen as a satin fabric is pointless. Damask (see below) is a variation of satin that does not require large areas of surface "floats". It is seen in flax linen as a luxury textile. Lately there has been an enormous resurgence in flax linen textile production in north-eastern Europe (Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, etc.). These countries have lower labour costs than western Europe and can grow much of the flax they need for mass production themselves, resulting in reasonably low per metre textile costs to consumers. The very finest linens however still tend to come from western Europe, especially Belgium and Ireland, and these continue to command the highest prices. Here is a brief glossary of some of the types of linen textiles available:

Linen remains today both a luxury fabric and an important eco-friendly textile with wonderful qualities that can’t be matched by synthetics. It also has none of the concerning ethical issues attached to it that some other textiles may have. Fortunately, the unique characteristics and advantages of linen are becoming recognized by many modern consumers, and this amazing, ancient fibre is being appreciated once again for its enduringly beautiful qualities. Ramie (Boehmeria nivea)Ramie, also known as China grass, is a member of the botanical family Urticaceae, and is accordingly closely related to the common stinging nettle plant, Urtica dioica, which is well known in northern regions of the world. The family resemblance is hard to miss when the two plants are seen side-by-side: Whereas stinging nettle is a plant of north temperate regions, ramie is very much a sub-tropical plant that grows best in the more humid regions of the Orient. Like common nettle, but unlike flax, it is botanically a perennial (although stinging nettle plants die down each winter in the north and re-grow from the roots in spring). In areas where ramie is cultivated, the plant continues to grow throughout the year, being harvested more than once and re-growing from the base. The (western) botanical designation for ramie was given in honour of George Rudolph Boehmer (1723-1803), a professor of botany at Wittemberg, Germany. Its descriptive name, “nivea”, comes from the Latin “nivalis” meaning snow-white (think of Nivea cream). The reason for this name is that the fibres obtained after processing ramie are usually pure white, unlike flax linen, which ranges from a blond to greyish-beige colour.

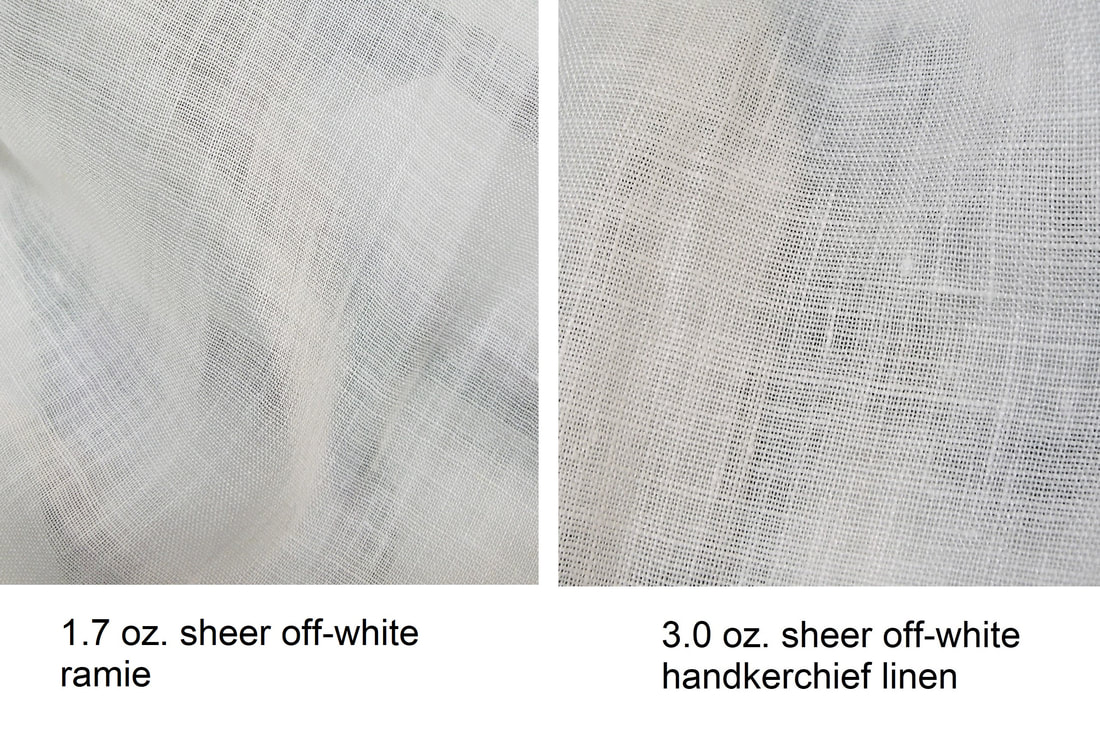

Ramie has many of the same properties as flax linen, such as high breathability, moisture absorbency, resistance to heat and washing, quick drying, and mildew resistance. Like true flax linen, it does soften with repeated washings, and does easily wrinkle. However, ramie also has a number of distinct characteristics, some of which are less desirable than flax. Ramie is stronger than flax or cotton, with longer, finer individual fibres. It dyes more easily than flax, holding its colour well despite exposure to sunlight, and has a visibly more lustrous sheen than linen made from flax, almost silk-like in fact, especially in lightweight ramie fabrics. Ramie, having very fine fibres without slubs, can be woven into cloth that is even finer and sheerer than the finest handkerchief (flax) linen. It is tougher and more durable than flax linen, good for hard-wearing applications. However, ramie has some unfortunate drawbacks for garment use, despite its being a natural textile. For one thing, its fine fibres, (unlike silk or wool, and more so than linen), are brittle and inflexible when dry, making spinning challenging, especially in mechanized settings. Secondly, ramie's relationship to the nettle plant is revealed in the tiny, bristly surface hairs of the fibres that remain on the fabric, even in the sheerest weaves. These are really only visible under a magnifying glass, but they cover the entire surface of the textile, making it very irritating for some people to wear next to the skin. The hairy surface of the fibres can also make high-speed industrial weaving problematic. Another negative aspect of ramie is the complex processing involved in going from plant to textile fibre. Unlike flax (which itself requires a series of steps to produce fibre for spinning), ramie stalks contain a gum-like substance which necessitates lengthy, additional beating, scraping, cooking at high heat, and chemical treatment to separate out and render the fibres usable for textiles. In turn, this reduces the economical production of cloth made from ramie and increases the cost of the finished product. The result is that, up until the past few years, modern ramie fabric has often been nearly as expensive as linen, and less available as a garment textile in the medium to heavier weaves. Recently however a bio-chemical, enzyme-based process has been introduced in China that may reduce the complicated, time-consuming process required to treat the plant material. If the processing problems can be solved, ramie’s strength and appropriateness for a number of garment, utilitarian and industrial purposes would make it a valuable cash crop for oriental producers. Still, much of the reason that ramie can compete price-wise with true flax linen on the international market, despite these processing complexities, is that ramie textiles are produced in countries with very low wages, sometimes appallingly so (or even child labour), in factories without the safety procedures and protections required in western countries by law. If China improves the ramie processing technology, allowing it to ramp up its ramie textile manufacturing, it will likely create a flood of ramie linen on the western market that, to the non-expert eye, will seem identical to flax linen but at a much lower price. At that point, flax linen production in northern regions may again be in serious jeopardy. As far as uses go, ramie is employed today to create many of the same end products as linen (except for the seeds and oil, since ramie is completely different botanically from linen). This includes rope, nets, utilitarian textiles, cloth for garments and furnishings, paper producing, and so on. The high durability and fineness of the fibres may make it valuable for industrial applications as yet undeveloped. In addition, like nettle leaves, the leaves of the ramie plant are edible, used in oriental cuisine. Historical availability of ramieAs mentioned earlier, ramie has a long history of use as a textile in the Orient. Since flax wasn't suitable for growing in these areas, even if it had been available, and there is little evidence that (unlike India) cotton was grown in any quantity in China or the south Asian regions, ramie was the most widely available plant textile. Like flax in northern regions of the earth, ramie textiles could be made on a small scale locally in the Orient, and hence it was available to the lower classes. Was ramie linen seen in Europe before the 20th century? It's not clear from my research whether ramie textiles were widely available outside the Orient prior to the early 1900's, although I have seen references to it in European publications of the Edwardian era. Still, since ramie, unlike flax, was inappropriate for growing in northern regions, and was similar to linen in many ways yet more difficult to process, it's likely that few ramie textiles and other products would have been imported all the way from southeast Asia. The end product simply wouldn't be able to compete with the more luxurious and comfortable flax linen textiles produced in Europe. Prior to the late 19th century, ramie textiles would doubtless have been at least as expensive as cotton from India, if not more so, given the complicated method of ramie fibre extraction combined with the long, difficult, and costly shipping from places like China. In effect, each part of the world had its own linen textiles: flax could not realistically be grown in humid tropical places, nor ramie in cool northern climates. But how do I tell them apart?Before approaching the question of identifying ramie from flax textiles, it's helpful to remember that the term "linen" itself has become generic, that is, applicable to cloth made from various plants. It's also been used to simply refer to the flax plant itself. The word "linen" does indeed derive from the name of the flax plant (linum), but is now generally applied to any bast textile, that is, one made from the phloem (inner layer) of natural plant fibres. Accordingly, there is flax linen, ramie linen, hemp linen, nettle linen, and even bamboo linen, all of them being lumped under the one designation, "linen", both by manufacturers and the clothing trade. The important point to remember is that generally speaking, flax and ramie are virtually impossible to distinguish from each other chemically once they're made into cloth, but the woven textiles themselves can often be identified based on their physical properties or characteristics. Recent research has shown that ramie and flax fibres may be able to be identified microscopically through a multi-faceted approach, an important factor for museums with historical textile collections. The obvious -- and serious -- issue arising from this reality is that a lesser quality linen textile (ramie) can masquerade as its more luxurious cousin (flax) on the worldwide consumer market. As mentioned above, if China succeeds in producing more ramie more quickly and of a higher quality at a lower price, it has the potential of destroying the northern flax linen market. Distinguishing true linen from ramie does take some experience and careful observation, but once you’ve handled the two fabrics side-by-side a few times, especially if they are of a similar weight, you’ll rarely need to wonder again. First, it should be said that a burn test is of no use in this context. Both textiles are are "bast" types, and will simply burn to a dry ash (like wood) in the same way. Basic chemical analysis to distinguish whether a woven textile is flax or ramie is essentially meaningless too, since both fibres will react to chemical reagents (such as strong acids or alkalines) in the same way. Both can be realistically and truthfully classified or labelled as "linen" by manufacturers and by the garment industry, complicating an already difficult problem. Only a complex lab analysis of impurities or chemicals in the fibres themselves -- a costly and time-consuming procedure at best -- might be able to determine the likely origin of the fibre, based on agricultural and processing chemicals used in different regions of the world. Many agrichemicals and pesticides are still legal in China and other far eastern countries that have long been banned in the West. Although such a lab analysis would be extremely expensive, it would not be able to conclusively identify the fibre, only point to the area of the world it probably came from. That is, if residues of certain agrichemicals used only in the far east were found, the textile would likely be ramie. I often use scent as a defining test to determine the content of fabric, but again, in this case both ramie and linen have that characteristic, wonderful fresh woodsy smell. So, what’s left to determine which is which? Well, the touch test, a keen eye, and a bit of textile knowledge. (1) Textile Knowledge: To begin with, much of what is sold today as the finest “linen voile” or even “super-fine handkerchief linen” is actually ramie. Generally speaking, true flax linen is not made in a weight lighter than about 3.0 oz. This is because modern linen fibres are not as fine as those of ramie. Accordingly, if you see linen fabric that is under about 2.8 oz. being sold, it is very likely to be ramie. As has been outlined above, knowing the source of the textile can be a help in identifying whether it's flax or ramie. This is where being able to rely upon information provided by seller or manufacturer is important (see further on). (2) A Keen Eye: Check for Slubs: If you’re buying from an online source, this may be somewhat difficult, but try to enlarge any photo of the fabric to a point where you can tell if there are slubs. If the fabric is said to be very lightweight (e.g. under about 2.8oz.) and has no slubs, it’s almost certainly ramie. If it’s over 2.8 oz. and you can see some slight slubbing in the weave, even in a handkerchief weight, it may be true linen. Heavier weights of true (flax) linen will almost always clearly display slubs in the weave in close-up photos. Look at the Sheen: Secondly, if you've purchased enough of the fabric to be able to pile it up on a table, look at it under good light, directed at an angle to the fabric. This test is especially useful if you can place a pile of yardage that you know to be true flax linen next to your mystery linen. Ramie linen almost always has a more definite surface sheen, sometimes almost a shine. Flax linen tends to have a much more subtle sheen, not as reflective as ramie. Check the Weave: A very close weave and some indication of a more pronounced lengthwise run in the fibres can signal that the fabric is woven from ramie. Although not conclusive in itself, this factor combined with other indicators, can help to positively distinguish ramie from flax linen. Most importantly, if you’re in doubt, ask the seller to confirm the content. If they can’t or won’t do so, either look elsewhere or order a swatch. A swatch may be the only way to know with more certainty, then see #(3) below. (3) The Touch Test: Once you have your swatch or have received your fabric order (or if you can touch and see the fabric close-up in person), first check for slubbing in the weave. An extremely lightweight, sheer fabric with a pronounced surface sheen and a very fine, smooth, slub-free weave will almost always be ramie. Testing for "bounce": Place the "mystery" fabric loosely in a pile on a table -- this works best with at least a half metre/half yard of fabric, to give you enough to manipulate. Gently scrunch a section of it up in your hands. Feel the character of the fabric as you do so: ramie will display a fair resistance to being bunched up, and a definite bounciness or tensile resiliency. However, this is a test that is really best as a comparative one. Place a length of fabric that you know to be true flax linen, preferably of the same weight of weave, in a pile next to the "mystery" fabric and handle it in the same way. Linen will display less resistance to being "scrunched up", will not bounce away from the hand as sharply, and will have an overall softer, more pliable feel (referred to as the fabric's "hand"). Testing Drape: Test the drape of the "mystery" fabric, preferably compared to a similar weave of true flax linen. To do this, hold the fabric up and with your fingers make a few knife-pleats across one cut end of the yardage, each pleat about 2 or 3cm (about 1") wide, across the width of the fabric (that is, along one cut end, working from selvedge to selvedge). Pin the pleats in place if you like, then hold up the piece and carefully observe how the pleats fall (or drape). Undo these pleats, turn the fabric piece, and make pleats of the same size in the other direction (that is, along the length of the piece, pleating along the selvedge). Again, observe carefully. Repeat this experiment with the length of fabric you know to be flax linen. What you'll find, if your "mystery" linen is ramie, is that the pleats will fall very nicely fairly flat, and with little resistance when made across the width of the fabric, but will create deep, springy, rounded folds when you try to pleat along the length (i.e. along the selvedge). By comparison, flax linen textiles will almost always pleat evenly and with little resistance in either direction. The reason for this is simple: ramie textiles are made from finer, longer fibres than flax linen, and therefore fabric woven from 100% ramie will have a strong lengthwise grain, compared to flax linen. You can often see this pronounced lengthwise weave in ramie fabrics simply by looking at them at an arm's-length distance, whereas flax linen tends to be fairly evenly woven in both directions. Ramie is also often more closely and stiffly woven than linen, sometimes to the point where lighter weights of ramie linen may actually have an organza-like "hand" or feel. Surface Feel: And here’s the final test: take a fairly large section of the fabric and very, very gently run the palm of your hand over the surface, preferably lengthwise on the fabric, then do the same with the back of your hand. If you feel a slightly bristly, hairy surface, almost like a peach-fuzz effect, you probably have ramie. If you can’t feel this with your palm, run the fabric gently against the inside of your forearm or your cheek – these areas of skin may be more sensitive to the prickliness of the surface of ramie. Once again, if you can compare this test immediately with a length of true flax linen, the difference will be apparent, especially if you have sensitive skin. Some people can't bear the feel of ramie against their skin unless the fabric is washed several times and put through a hot dryer, something that is entirely unnecessary with flax linen. (4) Linen Weights, Source, and Prices as Distinguishing Factors: Keep in mind that most ramie that is sold as “linen” in North America will be the sheerest, most transparent and lightest weight type. This is often the type that can compete most economically with flax linen, which can’t be produced in such extremely fine weights. The price of most of these featherweight ramie textiles may be close to that of true linen, so cost is rarely a helpful factor in identifying ramie. However, as mentioned above, as more ramie becomes more easily produced, especially in China, and as the quality and variety of ramie textiles increases, unfortunately it may become more and more difficult to know exactly what you're buying. These Chinese products can legally be sold as natural "linen", which doesn't help the consumer at all. Price may ultimately be your best clue: if you find light to mid-weight fabric being sold as natural linen, but at 30% or more under the usual prices of European linen, chances are very good the fabric is Asian ramie. Some sellers will correctly identify ramie fabric as such, others either don’t know enough to know the difference between ramie and linen or prefer not to say, for obvious reasons. Chinese/Asian or European? A reliable, trustworthy retailer should be willing to tell you where they source they "linen", even if they don't know the fibre content for certain. If that source is China or another country in the far east, and the price is lower than most European linen on the market, then the fabric is very likely to be ramie. If the seller confirms the fabric comes from a European or North American source, then it is most probably true flax linen. However, be aware that there are instances where true flax fibre is exported from northern European countries into countries (such as China) with cheap labour, to be made into linen textiles. In these cases, the source of the finished fabric will not help identify whether it's ramie or linen -- you will need to rely on one or more of the other physical properties tests mentioned above. If you're dealing with an honest, forthright textile retailer then at least you can make an informed decision as a consumer whether to buy the product or not. If the seller either can't provide details, or refuses to give more information, it's best to move on rather than being disappointed with your purchase. What to do with ramie?Even if it isn’t true flax linen, and if you may not be able to tolerate wearing ramie against your skin, that doesn’t mean that ramie has no uses in garment-making, even for historical items. For example, a fine, sheer ramie might make a wonderful 18th century cap, apron, engageantes, neckerchief, or even a cool, comfortable petticoat or under-petticoat for summer. It might be ideal for Victorian collars, cuffs, or bouffant sleeves, or a pretty fichu. It might also be the best fabric to use for Renaissance or earlier veils, cauls, wimples and ruffs. For the Edwardian/1910’s era, the finest lightweight ramie could be used in place of ultra-expensive Swiss batistes for summer lingerie gowns (as long as they are being worn over the usual soft cotton batiste underclothing, and not directly against the skin). Treating ramie to soften itIf you're sensitive to the itchy, bristly feel of newly-purchased ramie against your skin (as I am), it is possible to "beat down" the fabric's surface to a point where it's tolerable to wear. This type of extreme treatment is something I would never do with flax linen (it would produce a limp, flannelette-like result), but it does help to soften ramie linen's stiff and hairy texture. By the way, as an interesting test of the "before" and "after" state of the fabric, gently stroke the ramie fabric over your cheek or the inside of your upper arm now, then do the same after this treatment -- I think you'll easily feel the difference! Here is what I do, which will essentially help destroy some of the natural properties of the ramie: 1) Wash the piece in warm water first, preferably in a washing machine, not by hand, so that it gets some agitation. Don't use a "gentle" cycle, just a normal one. Let the machine spin-dry the fabric. 2) Wash it again in the machine, this time in slightly warmer water with a good, strong laundry detergent (like Tide with Oxyclean). Put it through the normal cycle again, spin-drying at the end. 3) Put the whole piece into the dryer on medium heat for about 40 minutes. You'll notice this will produce an enormous amount of lint -- this is the surface of the ramie fabric which has been abraded and sloughed off during this process (including a lot of the bristly bits of fibre). 4) Iron the fabric. Use an iron set to the highest (linen) heat setting. Spritz each section of the fabric with water before ironing, then firmly press as you iron. Repeat over the entire length of fabric. Air-dry on a rack before storing. And try the cheek-stroking test again. I guarantee it will feel like a different fabric! Perhaps not quite as soft and comforting as flax linen, but acceptably soft enough to wear against the skin. The following series of photographs may help you to be able to recognize some of the visual differences between linen and ramie the next time you’re shopping for fabric. 1. In the photo below, I’ve put a length of 1.7 oz. ramie (at the left) and 3.0oz. handkerchief linen (at the right) next to each other. Scissors were placed under each of the fabrics to demonstrate their relative sheerness for the given weight. It’s fairly clear from this picture that the ramie is visually more sheer than the linen. 2. Below is a photo of the ramie on its own. Notice the evenness, closeness of weave, and smooth, fine texture of the fabric: 3. Compare the above photo of ramie to this photo of the handkerchief linen shown earlier. Notice the slubs, even in this very fine 3oz. handkerchief linen:

5. When the ramie (at left) and linen (at right) are placed side-by-side in a close-up, the difference in fibre thickness, slubbing (or lack of slubbing where the ramie is concerned), and closeness of weave are fairly clear, especially for anyone used to working a lot with flax linen. These photos were taken at the same distance. (Scissors were placed under each piece to demonstrate the relative sheerness of the fabrics). 6. Below is a photo of some 2.0oz. sheer ramie yardage in a steel blue colour, showing the almost silk-like sheen of the cloth and the even texture and weave. True linen has a much more subtle surface lustre and is not available in such very light weights. You may also be able to tell from the photo how much this piece of ramie linen reacts like organza when scrunched up (portion at right in the picture). 7. Next is the same ramie textile a little closer up, showing its fine, close, even, semi-transparent weave. Notice the very fine, hair-like fibres at the selvedge, much finer than those of flax linen. Note also the more pronounced lengthwise grain of this fabric as compared to the handkerchief linen shown earlier. How is the weight of linen textiles measured?The weight of both linen and ramie textiles is expressed in either grams per square metre (“gsm” in the metric system used by most of the world), or ounces (oz.) per yard for U.S. measurements. This gives a very good indication of the weight, thickness (or hand) and the sheerness or opacity of the fabric. However, keep in mind that the more open the weave, the more the fabric will have a gauze-like, less opaque character in any weight. Accordingly, the number of threads per inch/centimetre are also important in understanding the character of the cloth. For example, a handkerchief linen with 30 threads per inch will be sheerer than one with 40 threads per inch, even though the textiles may be described as being of a similar gsm or oz. weight. The following summary (given in both measurements) provides a rough guide to the types and best uses of the various weights of ramie and linen: About 1.5 to 2.8 oz. (Less than about 90 gsm) Linen textiles of this weight will almost always be finest, sheer ramie cloth, sometimes called “linen voile” or “ramie voile”. Has a sheen and springiness similar to silk organza. Unlikely to be flax linen. For sheer blouses or accessories such as cuffs, collars, handkerchiefs, aprons, table linens, etc. Takes to embroidery well. May be difficult for some to tolerate next to the skin. Over 2.8 to about 3.5 oz. (approx.. 90 – 120 gsm) This is fine handkerchief linen weight (although a 2.8 oz. true flax linen is very rare); Semi-sheer, soft, drapes beautifully, lightweight, extremely smooth and comfortable against the skin. For fine lingerie, blouses and accessories; unmatched for use in items worn next to the skin, especially good for 18thC. reproduction shifts. Very desirable for 18thC. style caps, handkerchiefs, aprons; 19th & early 20thC. reproduction blouses and dresses; some types of lingerie. About 4 to 8 oz. (approx. 130 to 190 gsm) This is the mid-weight of most true linens, with a very wide range of uses and weaves. Generally semi-opaque to fully opaque. The lighter, 4 to 5 oz. weights are especially good for 19th & 20thC. reproduction blouses and summer dresses, and for 18thC. linings, gowns and petticoats. The heavier types in this category (6 or 7 oz) are best for jackets, stays (18thC.), or more substantial dresses, skirts and outerwear (19th & 20th C.). Some weights in this category, including the twill weaves, are well suited to certain home decorating uses, such as bed linens, curtains, lighter weight upholstery, towels, etc. About 9 to 16 oz. (over 200 gsm) Considered heavy weight linen, these types are rarer on the retail fabric market. Includes such textiles as linen canvas and heavier twills. Very thick, stiff and usually with little drape. Best for the most substantial outerwear (below 12 oz.), such as Edwardian automobile "dusters", or 18thC. support layers that require both sturdiness and breathability. Generally mostly used for upholstery or decorating purposes, book-binding, etc.; Linen canvas is the traditional base material for fine oil paintings. Handling and Cleaning Ramie and LinenRamie and true linen can be dealt with in the same way for most purposes. Both will shrink significantly (3% or more) when washed, so my first advice is to always, without fail, pre-shrink ramie or linen fabric before you sew with it. Unless you enjoy the crisp, rather stiff vertical hand and bristly surface of ramie as it comes from the bolt, pre-treating it as described earlier to soften it will tame its less desirable characteristics and at the same time ensure it is thoroughly pre-shrunk. Do not give true flax linen the same brutal treatment, unless you really prefer to turn it into a limp, fluffy fabric similar to cotton flannelette. Otherwise, both flax and ramie linen can be handled similarly: To Pre-Shrink: Soak the linen or ramie yardage in cold to medium-hot water for at least 30 minutes, and preferably up to an hour, leaving it undisturbed (i.e. don't put it through a washer cycle). The water temperature you use for pre-shrinking should be similar to the temperature you plan to use for future washing. Carefully lift the fabric out of the water, and allow the bundle to drip for a minute or two to release excess water. Avoid hard wringing or twisting, as this will encourage wrinkling. Or, if you are pre-shrinking in an automatic washer, put the fabric through the spin cycle (but remove the fabric immediately after the spinning is finished, to prevent hard wrinkles from setting). Dry the ramie or linen on a drying rack, smoothing the fabric as much as possible. Leave to drip until almost, but not quite dry, preferably outside on a clear, dry day if possible. Linen and ramie can be put through the dryer on a medium-low setting, but be aware that this treatment will change the character of the cloth, making the surface fluffier and less crisp. After Pre-Shrinking: One key point with ramie and linen is to try to catch the fabric before it's completely dry if you want to be able to iron it smooth without difficulty. Ideally, the fabric should still be slightly damp, but definitely not wet. Use a dry iron on the "cotton" or "linen" setting to press out any wrinkles and smooth the yardage. Then be sure to hang the yardage for a few hours, preferably outdoors, to ensure it's completely dry before storing it. Cleaning: Both ramie and linen garments can be dry-cleaned, but it's hardly worth the cost unless the garment is a complex or tailored item that will make ironing it after washing a real challenge, if not impossible. However, for items of fairly simple construction, such as shirts, skirts and lingerie, reproduction shifts, petticoats, etc. washing is the best choice. Linen and ramie can take hard, frequent washing, and in fact will become softer with time if so treated. As noted above, they can be put in the dryer if you're willing to change the way they drape and feel. But if you want to keep your linen garments crisp-looking, gentle washing and drip-drying is best. I wash my 18th century reproduction linen shifts and men's linen shirts (both made of true flax linen) in the automatic washer on the gentle cycle, with a mild soap (like Woolite or Zero), and hang them outside to almost dry. I then iron them while still slightly damp to get a perfectly beautiful result. There is nothing like the wonderful scent of freshly-washed linen brought in from outside on a breezy summer's day. In fact, this is precisely the scent some commercial air freshener products attempt to capture "in a bottle"! Storing: If properly stored in a dry, clean place with reasonably good air circulation, linen garments will last beautifully for decades (even centuries). Moths are not an issue at all (they are interested in protein fibres, not plant material). However, too much dampness for too long can encourage mold. For this reason, always be sure linen garments and fabrics are thoroughly dry before storing. If you're planning to store linen yardage folded up for more than a few months, whether ramie or flax linen, it's a good idea to take it out from time to time to air the fabric and release wrinkles. If you have time, give it a brief pressing with a steam iron, then air-dry for a few hours. Fold it differently when replacing into storage, to avoid permanent creasing along old fold lines. A Note About Safety: Both linen and ramie, being plant-derived, are easily flammable, so be careful about wearing linen garments near open flame (this is especially true where historical reproduction gowns with trains or wide hemlines are concerned). A Gallery of Historical Replicas in Linen:Following are some examples of historical items I've created over the years using various weights of true (flax) linen. Linen remains one of my favourite textiles to sew with and to wear! Using linen for historical reproductions:True (flax) linen is especially historically accurate for 18th century reproduction garments and under-garments. There is certainly no textile better than flax linen to accurately replicate 18thC. shifts. But linen is also just as perfectly suited to the 19th and early 20th century, keeping in mind the appropriate fabric weight and drape for the particular use. For example, mid-weight (suiting weight) linen was highly fashionable and widely used for walking suits and summer day dresses during the 1908 to 1919 era. But linen is of course also appropriate for Renaissance, Elizabethan, medieval, and ancient representations, and its uses for fine accessory garments is virtually endless. Since linen's use in garment-making goes back millennia, for both upper and lower classes, the possibilities are unlimited. I hope this guide will provide some insights into these two textiles and help you choose just the right fabric – whether ramie or true flax linen – for your next project.

Upcoming topic: Silks and the Faux Silks.

4 Comments

Judy

15/9/2021 08:05:30 pm

Very detailed and informative! I agree that more education about textiles and their sources is much needed. Until I began historical costuming, I had a minimum understanding of textiles. While I had been sewing for many years prior to beginning historical costuming, I really didn't understand the qualities of the fabrics I was using, nor did I realize how much choosing a fabric for how it would "behave" affected the finished garment in appearance and function. Am looking forward to your next installment in this series!

Reply

27/8/2022 04:21:57 am

Nice Post! Thanks for sharing a great post. I really liked it.

Reply

kate

10/4/2023 11:04:42 am

should i buy a much larger clothing size in a ramie piece so when washed and it shrinks it'll fit (maybe??)

Reply

Patricia

11/4/2023 03:36:44 pm

Off-the-rack clothing should always have a care tag indicating how they should be washed or laundered. If you don't see a care tag, it's best not to buy the garment. Individual clothing manufacturers have different processes -- some will use only pre-shrunk fabrics, others will make their garments from textiles that have not been pre-shrunk.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPatricia Preston ('The Fashion Archaeologist'), Linguist, historian, translator, pattern-maker, former museum professional, and lover of all things costume history. Categories

All

Timeline

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed