|

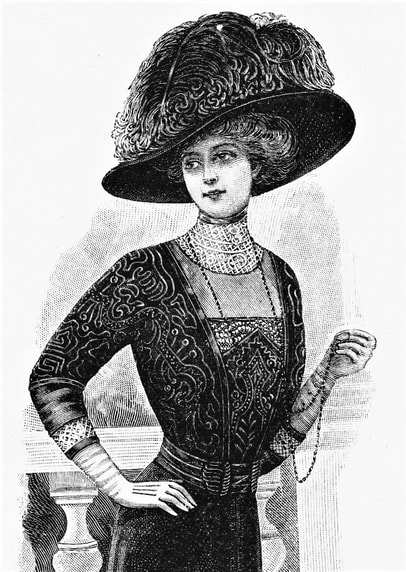

If one element of women's fashion defined formal daytime elegance during the Edwardian era, it was the high, fitted, boned collar. Unlike their rigid, often plain, Victorian predecessors, the Edwardian boned collar was usually a thing of delicacy and charm, made of fine materials such as lace, chiffon, silk net, or lightweight linen, boned in narrow whalebone, featherbone, or (later) fine zig-zag wires. I've seen all these types in both museum examples and in pieces in my own collection of antique garments, although I have not seen steel bones of any kind used in Edwardian collars. Being able to construct one of these iconic period collars is a key part of creating an ensemble that reflects the time period accurately. I see many sewists struggling with this aspect of historical construction, and am hoping my insight and experience can help! (Please click on "Read More" at right, to see the full tutorial) First, a little background. This type of lovely, delicate boned collar began to appear toward the very end of the 1890's, but really came into high fashion after about 1901, when lighter, more softly draping materials became the norm in daytime dresses and blouses. Virtually all dresses and blouses worn during the day had a high boned collar. Open necklines were considered only appropriate for evening wear during the early Edwardian years (although this changed later on). As the decade progressed, the boned high collar was everywhere, including on the better quality "lingerie" blouses. From about 1906 to 1912, boned collars on day gowns or silk or wool blouses tended to be made of the most delicate materials possible: silk chiffon, lightweight lace, and fine silk net being especially favoured, often with horizontal pleating, insertion lace, and a frill of lace along the top. Many of these collars were small works of art in themselves. Around 1910, and throughout 1911 and 1912, open (collarless) necklines began to become accepted as appropriate on many daytime dresses and blouses, especially for summer wear. Boning was also frequently omitted on less formal linen or cotton summer blouses or dresses that did have high collars. Generally though, a high boned collar would still be part of a more dressy or formal blouse or day gown, especially those made of silk or wool. Somewhere around 1913, open necklines (that is high, round or squared necklines) began to be more common for daytime wear than necklines with high boned collars, and even open "V" necklines became acceptable. By the WWI period the delicate lace, net or chiffon high boned, closely-fitting collar more or less disappeared from fashion, replaced by the Medici-style collar or sailor collar with an open V-neck. Fashion presumably recognized that, given new freedoms out of necessity during WWI, women liked the more comfortable styles and no longer wanted to be the tightly-bound, restricted creatures they had been previously, always requiring someone else to dress them. Yet the high, boned, fitted collars of the Edwardian era had their charms, certainly not the least of which was their ability to set off and enhance a face framed by a magnificent hat. In this, these collars had much in common with the Elizabethan ruffs of the late 1500's and early 1600's, or the handkerchiefs and fichus of the 18th century. Constructing a Classic Edwardian Boned Collar. Making a classic Edwardian boned collar is essentially a matter of layers. In most original Edwardian collars (for example, those made of net or lace), the boning was "sandwiched" between fine layers of chiffon, net or silk, partly to prevent the bones from being too visible from the outside, and partly to provide a soft layer of chiffon against the neck, rather than having the skin in direct contact with the bones or boning tapes. In some later garments (towards 1908 and onward), zig-zag wires rather than boning was used as stiffening, inserted into channels made from sheer chiffon, net or silk, or else directly whip-stitched loosely into place. Often these wires were sold pre-wrapped in silk floss or thread to soften their surfaces and prevent direct contact with textiles or skin. Either type of stiffening method can be used today (the spiral wires can still be purchased, or made by hand from non-rusting fine wire). However, I find that narrow plastic boning is simplest to work with and does a fine job of replicating the antique type. The following steps set out a technique modified for modern use which I've developed from many years of studying extant Edwardian garments and constructing replicas. This "sandwich" method can be used with virtually any combination of typical Edwardian/1910's delicate fabrics, such as a lace or net collar with chiffon or organza inner layers, either with boning or wire stiffeners. I prefer using silk organza for the inner collar layers, as it is lightweight and sheer yet strong, providing additional support throughout the collar. Silk chiffon or a fine net can be used for the two inner layers instead, although these will be somewhat more demanding to work with. The reason for two inner layers is that one is used to hold the boning, but with its good side lying smoothly against the collar's fashion fabric, and the second layer provides extra inner support for the collar. The second layer can be omitted if you wish, especially if you are making a collar out of very fine, sheer fabric such as chiffon, where the weight of an extra layer might actually make it more difficult to keep the collar staying upright when worn. The example shown in the photo tutorial that follows here is a boned linen collar, with two inner support layers of organza (one of which -- the one closest to the outside layer of the collar -- is boned). The collar lining in this example, which is the layer next to the neck when worn, is of fine handkerchief linen, but for a lace or net collar might be made of China silk or chiffon. The collar shown forms part of a 1912 dress available as History House pattern #1912-A-016, which can be purchased at the link below. The first step in making a boned Edwardian collar is to decide on the type and width of boning to use. I like to start with 7mm wide German Plastic Boning (the type with visible ridges -- see photo below), and cut about a 20cm (8") long piece. Then I carefully cut the piece lengthwise between the ridges, to create two very narrow 20cm (8") lengths of boning about the width of the historical fine whalebone used in collars of the era. If you can't obtain German Plastic Boning, then "synthetic" or "faux" whalebone (a plain plastic boning) will do, but may be a little more difficult to cut into narrow lengthwise strips. In that case, I'd advise buying the narrowest width you can find, which is usually 5mm. A 7mm width will work, but will make your collar stiffer. For the average boned collar, you'll need six 5cm (2") long pieces of boning. If you plan to bone the two back edges of the collar, you'll need 2 more bones. Instead of boning, you can make your own "zig-zag wire" collar stiffeners, although this requires more effort and time. Cut fine rust-free steel wire into approximately 8.0cm (3") lengths, then with pliers bend each along its length to create wave-like shapes, forming a narrow band (no wider than about 1.0cm [3/8"]). The photos below show a sample of a modern purchased "zig-zag wire" that has been cut to the desired length for use and one end bent in already. It is essentially the same as the collar wires sold in the 1910's. I like to use these wires on collars made of the finest, sheerest materials, as they are less visible from the outside than the synthetic boning. Be careful to bend in each end of the wire tightly with pliers to prevent it poking through into your neck once it's in the collar! Another option would be to make your own featherbone (assuming you have access to natural feathers with quills of the right type and width). If you make your own featherbone, you'll need to be prepared to do some experimenting to get the proper "spring" vs. stiffness and strength. Frankly, there is little advantage to using featherbone over finely cut German Plastic boning. Once you've cut and prepared your boning (or zig-zag wires), the next step is to cut all the layers you'll need to create your collar. In the following photos, for this linen collar, I've cut one layer of dress-weight (fashion fabric) linen, two layers of silk organza (which will be the inner layers of the "sandwich"), and one layer of lining fabric (in this case I used fine, lightweight handkerchief linen, but China silk, lightweight taffeta, silk satin, or cotton batiste would also work well). Take one of the organza collar sections and lay it on a flat surface. Mark with pins or fade-fast marker your desired bone positions. This is largely a matter of personal preference, but the pattern of boning shown below is typical of an early 1910's boned collar -- one on each side of centre front, one on each side of the neck, and one on each side (but not too close to) of what will be the centre back of the gown or blouse. Remember that you will need to leave sufficient allowance at each end for finishing and about a 4.0cm (1-1/2") overlap for closure. If desired, you can also cut two bones to be used to stiffen the two back ends of the collar. I find this is generally unnecessary unless I'm constructing a collar of chiffon, net, or fine lace, in which case the two back bones will help to support the centre back closures and keep the collar upright at the back. Next, cut your boning tapes: I like to use bias-cut strips of silk organza about 3.5cm (1-1/4") wide, folded in half lengthwise, which works well with my narrow-cut plastic boning. Historical garments often had bones inserted into narrow silk grosgrain ribbon, which is almost impossible to find today, although silk satin ribbon is an alternative. However I find the bias organza bends and shapes nicely without wrinkling, and is sheer enough to be almost invisible for all but the sheerest collars once encased in the collar layers. You can use anything else for boning channels that is lightweight and relatively inconspicuous, such as bias-cut China silk or modern seam binding in a colour matching your collar. However, be sure you test a sample of your planned boning tape to be sure your boning will fit into it once the tape is sewn. This will save you unnecessary grief later on. Pin each boning tape onto one side of the organza piece at your boning marks. With organza, chiffon, or silk net as this layer, it really doesn't matter which side of the fabric you choose to pin the tapes to, just be sure to pin them all on the same side. However, some fabrics (such as certain satins for example) may have a good and a wrong side -- pin the tapes to the wrong side. Keep in mind that the photos above show a shaped collar for a 1912 day gown. Dressy gowns from about 1909 and later generally closed at centre back, but earlier gowns usually had complex, asymmetrical closures, with the collar being permanently attached only on one side of the bodice front. Your gown pattern should guide you as to which type of construction is involved. I've included an example below of each type of closure as a reference. The first is an extant ca.1900 green printed silk gown with a complex front closure and a collar that is attached permanently on one side only, then brought around the other side of the front and to the centre back, to overlap and close. The second example is a 1910 replica dark green velvet gown with all closures at centre back. In this case the collar is permanently attached all the way around the neckline and open at centre back, where one end overlaps the other to close. Next, insert the bones into their channels/tapes, being certain to cut the bones to a length that allows some room at top and bottom, in other words, about 0.7cm (1/4") inside the top and bottom stitching lines. To permanently close the channels/tapes and secure the bones in place, stitch just barely inside the seam lines all around. If you plan to place two bones at centre back, you'll need to try on the collar for fit after the above bones are sewn in, but before the other collar pieces are added. Make any adjustments at the back edges on all layers of the collar before continuing. For example, you will need to check the overlap at centre back and allow for necessary finishing allowances. This may involve trimming away some excess or using some of the allowances already provided in order to increase fit. Finish Making the "Sandwich" Leaving the organza strip on a flat surface with the boned side facing up, lay the other two layers in place, with their good sides facing up: first the other organza layer, then the fashion fabric layer. Match raw edges and pin all three layers together. Important! If you plan to add lace insertion, tucking, or embroidery to the outside of the collar (fashion layer) this must be done first, before assembling the layers. When adding lace or embroidery, remember to leave sufficient room at the top and bottom edges of the fashion layer of the collar for seam allowances and finishing. For tucking, you will need to calculate the extra depth needed when cutting the outside (fashion) layer, to allow enough for the tucks. In 'History House' patterns, where tucking is required, instructions are given for making tucks in the material before cutting out the collar from the fashion fabric. On the other hand, if you plan to add a lace edging (frill) or a bias satin or velvet band to the top of the collar, this can be done after the collar is completed. Turn the entire stack over so that you can work from the underside of the first organza layer -- this makes it easier to see where the bones are and avoid nicking them with the machine needle when sewing. Stitch around the outside edges, just within the seam allowances, to secure the layers together. Now the only step remaining before mounting the collar to the gown is to sew on a lining. Pin the lining, right sides together, to the fashion layer along the top edge and stitch. Trim, grade, and clip the allowances, then turn the lining to the wrong side of the collar and press well. (The two short ends will be finished by hand after the collar is mounted to the garment and fitted to the wearer's personal preference). Next Steps: The collar can now be temporarily pinned to the garment neckline (do this from the outside), matching centre front points. Try on the garment with the pinned collar attached, and determine how you would like the back closure to be finished -- depending on the design of the garment, the two back edges of the collar can either overlap one over the other (by about 2.5cm [1"]), or meet together at centre back with no overlap (this is a more difficult finish to create a neat, firm closure). Mark the position of the finished edges with thread-tracing, then trim any excess, leaving a 2.0cm (3/4") allowance on each edge. If you've planned to add a bone along each back edge, do it now by encasing each bone in seam binding or silk satin ribbon folded lengthwise. Neaten each end of the binding or ribbon, then invisibly slip-stitch the finished, covered bone onto the back of the collar, keeping the lining free. Turn the allowances in on collar back edge and lining over the bones, and neaten the back edges by hand. If you plan to add a narrow velvet or satin trim to the top of the collar (a typical Edwardian/1910's touch), or a Valenciennes lace edging, this should be done now, that is, after the two back edges of the collar have been finished. Keeping the lining free, sew ribbon along both long edges, with the top edge as close as possible to the top of the collar. If you're using a bias strip of fabric, be sure to turn under both top and bottom raw edges when applying it to the collar. If you're adding a lace edging, you only need to attach the bottom edge of the lace to the top of the collar. It's best to sew the trim along the entire top length of the collar by hand, making the attachment stitching as neat and invisible as possible. Here are some photos of current 'History House' designs that have high boned collars, some of silk or linen, others of lace. All these authentic sewing patterns are available on Etsy (use the link below to browse). There were a number of different methods for boning collars during the Edwardian and 1910's era, most of them being fairly similar to the technique I've described above. However, some had creative alternatives to the usual boning methods and patterns, especially for very sheer, lightweight fabrics. Below are photos of a fine black wool bodice of ca. 1907-08 from my own collection, showing a rather unusual arrangement of the collar supports. In this case, the boning is featherbone, wrapped in silk, sewn on by hand into two "wishbone" shapes, with their tops encased in little silk "pockets". Although unusual, this method was probably not rare; I've seen these "wishbone" style arrangements in other extant bodices of this era. You could certainly create a similar support using very narrow strips of German Plastic boning, but I would recommend wrapping them in silk satin or China silk (as here) to prevent chafing against the neck. Often a sheer collar such as this would have an additional layer (lining) of chiffon or net on the neck side for this reason. The collar itself is made of black chiffon, finely tucked, and lined with just one layer of ecru coloured China silk, some of which has weakened and is falling away. The two back collar edges are supported with flat likely baleen bones, encased in ecru silk grosgrain ribbon. A fine black Valenciennes lace edging trims the top. The whole collar gives the most delicate impression, the tucked black-over-ecru chiffon being repeated on the bodice and sleeve cuffs. Edwardian and 1910's high boned collars were almost always sewn on by hand, and this is still the easiest method of getting a perfect finish and controlling the fabric. Mounting an Edwardian or 1910's collar to the garment neckline will be the subject of a separate tutorial, but I hope that the guidelines here will take some of the mystery away from making a beautiful, authentic-looking boned collar for your next Edwardian or 1910's dressy ensemble. Happy Sewing All!

1 Comment

Thank you so much for this, i was reading about an old, attempted murder in my French Lit studies and this mans "whale-bone collar" saved him having fatal wounds. Naturally, i had to see what that was, what an interesting article of clothing that is very helpful.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPatricia Preston ('The Fashion Archaeologist'), Linguist, historian, translator, pattern-maker, former museum professional, and lover of all things costume history. Categories

All

Timeline

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed